The New Testament and the FloodON THE GREAT FLOOD OF NOAHAfter the Flood by Bill CooperThere are many today who consider the early chapters of Genesis to be "historical myth." The story of Creation and the Flood didn't really happen--it is not a part of mankind's actual history they tell us. It is a legend or a story derived from various sources but these events never took place. Jesus did not hold to this view. He frequently quoted Genesis, speaking from it with the same regard and authority He gave to all the rest of Scripture. The Apostles of Christ also held to the authority of the Old Testament as God's Word, as historically accurate. The Apostle Peter devotes a good portion of his second Epistle to a warning concerning false teachers and skeptics who distort or deny the fact that God has intervened radically in human history will do so again in the near future.  The late William Barclay offers the following comments on Peter's second letter which deals with the general subject of false teaching, and brings forth a number of Old Testament illustrations, including the Flood of Noah. THE PASTOR'S CARE

Here speaks the pastor's care. In this passage Peter shows us two things about preaching and teaching. First, preaching is very often reminding a man of what he already knows. It is the bringing back to his memory that truth which he has forgotten, or at which he refuses to look, or whose meaning he has not fully appreciated. Second, Peter is going to go on to uncompromising rebuke and warning, but he begins with something very like a compliment. He says that his people already possess the truth and are firmly established in it. Always a preacher, a teacher or a parent will achieve more by encouragement than by scolding. We do more to reform people and to keep them safe by, as it were, putting them on their honour than by flaying them with invective. Peter was wise enough to know that the first essential to make men listen is to show that we believe in them. Peter looks forward to his early death. He talks of his body as his tent, as Paul does (2 Corinthians 5:4). This was a favorite picture with the early Christian writers. The Epistle to Diognetus says, "The immortal soul dwells in a mortal tent." The picture comes from the journeyings of the patriarchs in the Old Testament. They had no abiding residence but lived in tents because they were on the way to the Promised Land. The Christian knows well that his life in this world is not a permanent residence but a journey towards the world beyond. We get the same idea in verse 15. There Peter speaks of his approaching death as his exodos, his departure. Exodos is, of course, the word which is used for the departure of the children of Israel from Egypt, and their setting out to the Promised Land. Peter sees death, not as the end but as the going out into the Promised Land of God. Peter says that Jesus Christ has told him that for him the end will soon be coming. This may be a reference to the prophecy in John 21:18, 19, when Jesus foretells that there will come a day when Peter also will be stretched out upon a cross. That time is about to come. Peter says that he will take steps to see that what he has got to say to them will be held before their memory even when he is gone from this earth. That may well be a reference to the Gospel according to St. Mark. The consistent tradition is that it is the preaching material of Peter. Irenaeus says that, after the death of Peter and Paul, Mark, who had been his disciple and interpreter, handed on in writing the things which it had been Peter's custom to preach. Papias, who lived towards the end of the second century and collected many traditions about the early days of the Church, hands down the same tradition about Mark's gospel: "Mark, who was Peter's interpreter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, all that he recollected of what Christ had said or done. For he was not a hearer of the Lord, or a follower of his; he followed Peter, as I have said, at a later date and Peter adapted his instruction to practical needs, without any attempt to give the Lord's words systematically. So that Mark was not wrong in writing down some things in this way from memory, for his one concern was neither to omit nor to falsify anything that he had heard." It may well be that the reference here means that Peter's teaching was made still available to his people in Mark's Gospel after his death. In any event, the pastor's aim was to bring to his people God's truth while he was still alive and to take steps to keep it in their memories after he was dead. He wrote, not to preserve his own name, but the name of Jesus Christ.

Peter comes to the message which it was his great aim to bring to his people, concerning "the power and the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ." As we shall see quite clearly as we go on, the great aim of this letter is to recall men to certainty in regard to the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. The heretics whom Peter is attacking no longer believed in it; it was so long delayed that people had begun to think it would never happen at all. Such, then, was Peter's message. Having stated it, he goes on to speak of his right to state it; and does something which is, at least at first sight, surprising. His right to speak is that he was with Jesus on the Mount of Transfiguration and that there he saw he glory and the honour which were given to him and heard the voice of God speak to him. That is to say, Peter uses the transfiguration story, not as a foretaste of the Resurrection of Jesus, as it is commonly regarded, but as a foretaste of the triumphant glory of the Second Coming. The transfiguration story is told in Matthew 17:1-8; Mark 9:2-8; Luke 9:28-36. Was Peter right in seeing in it a foretaste of the Second Coming rather than a prefiguring of the Resurrection? There is one particularly significant thing about the transfiguration story. In all three gospels, it immediately follows the prophecy of Jesus which said that there were some standing there who would not pass from the world until they had seen the Son of Man coming in his kingdom (Matthew 16:29; Mark 9:1; Luke 9:27). That would certainly seem to indicate that the transfiguration and the Second Coming were in some way linked together. Whatever we may say, this much is certain, that Peter's great aim in this letter is to recall his people to a living belief in the Second Coming of Christ and he bases his right to do so on what he saw on the Mount of Transfiguration. In verse 16 there is a very interesting word. Peter says, "We were made eye-Witnesses of his majesty." The word he uses for, eye-witness is epoptes. In the Greek usage of Peter's day this was a technical word. We have already spoken about the Mystery Religions. They were all of the nature of passion plays, in which the story of a god who lived, suffered, died, and rose again was played out. It was only after a long course of instruction and preparation that the worshiper was finally allowed to be present at the passion play, and to be offered the experience of becoming one with the dying and rising God. When he reached this stage, he was an initiate and the technical word to describe him was epoptes; he was a privileged eye-witness of the experiences of God. So Peter says that the Christian is an eye-witness of the sufferings of Christ. With the eye of faith he sees the Cross; in the experience of faith he dies with Christ to sin and rises to righteousness. His faith has made him one with Jesus Christ in his death and in his risen life and power. THE WORDS OF THE PROPHETS So this makes the word of the prophets still more certain for us; and you will do well to pay attention to it, as it shines like a lamp in a dingy place, until the day dawns and the Morning Star rises within your hearts. For you must first and foremost realize that no prophecy in Scripture permits of private interpretation; for no prophecy was ever borne to us by the will of man, but men spoke from God, when they were carried away by the Holy Spirit. (2 Peter 1:19-21) This is a particularly difficult passage, because in both halves of it the Greek can mean quite different things. We look at these different possibilities and in each case we take the less probable first. (i) The first. sentence can well mean: "In prophecy we have an even surer guarantee, that is, of the Second Coming." If Peter did say this, he means that the words of the prophets are an even surer guarantee of the reality of the Second Coming than his own experience on the Mount of Transfiguration. However unlikely it may seem, it is by no means impossible that he did say just that. When he was writing there was a tremendous interest in the words of prophecy whose fulfillment in Christianity was seen to prove its truth. We get case after case of people converted in the days of the early church by reading the Old Testament books and seeing their prophecies fulfilled in Jesus. It would be quite in line with that to declare the strongest argument for the Second Coming is that prophets foretold it. (ii) But we think that the second possibility is to be preferred: "What we saw on the Mount of Transfiguration makes it even more certain that what is foretold in the prophets about the Second Coming must be true." However we take it, the meaning is that the glory of Jesus on the mountain top and the visions of the prophets combine to make it certain that the Second Coming is a living reality which all men must expect and for which all men must prepare. There is also a double possibility about the second part of this passage. "No prophecy of the Scripture," as the Revised Standard Version has it, "is a matter of one's own interpretation." (i) Many of the early scholars took this to mean: "When any of the prophets interpreted any situation in history or told how history was going to unfold itself, they were not expressing a private opinion of their own; they were passing on a revelation which God had given them." This is a perfectly possible meaning. In the Old Testament the mark of a false prophet was that he was speaking of himself, as it were, privately, and not saying what God had told him to say. Jeremiah condemns the false prophets: "They speak visions of their own minds, not from the mouth of the Lord" (Jeremiah 23:16). Ezekiel says, "Woe to the foolish prophets who follow their own spirit, and have seen nothing" (Ezekiel 13:3). Hippolytus describes the way in which the words of the true prophets came: "They did not speak of their own power, nor did they proclaim what they themselves wished, but first they were given right wisdom by the word, and were then instructed by visions." On this view the passage means that, when the prophets spoke, it was no private opinion they were giving; it was it revelation from God and, therefore, their words must be carefully heeded. (ii) The second way to take this passage is as referring to our interpretation of the prophets. A situation was confronting peter in which the heretics and the evil men were interpreting the prophets to suit themselves. On this view, which we support, Peter is saying: "No man can go to Scripture and interpret it as it suits himself." This is of first-rate practical importance. Peter is saying that no man has the right to interpret Scripture, to use his own word, privately. How then must it be interpreted? To answer that question we must ask another. How did the prophets receive their message? They received it from the Spirit. It was sometimes even said that the Spirit of God used the prophets as a writer uses a pen or as a musician uses a musical instrument. In any event the Spirit gave the prophet his message. The obvious conclusion is that it is only through the help of that same Spirit that the prophetic message can be understood. As Paul had already said, spiritual things are spiritually discerned (I Corinthians 2:14, 15). As the Jews viewed the Holy Spirit, he has two functions--he brings God's truth to men and he enables men to understand that truth when it is brought. So, then, Scripture is not to be interpreted by private cleverness or private prejudice; it is to be interpreted by the help of the Holy Spirit by whom it was first given. Practically that means two things. (a) Throughout all the ages the Spirit has been working in devoted scholars who under the guidance of God have opened the Scriptures to men. If, then, we wish to interpret Scripture, we must never arrogantly insist that our own interpretation must be correct; we must humbly go to the works of the scholars to learn what they have to teach us because of what the Spirit taught them. (b) There is more than that. The one place in which the Spirit specially resides and is specially operative is the Church; and, therefore, Scripture must be interpreted in the light of the teaching, the belief and the tradition of the Church. God is our Father in the faith, but the Church is our mother in the faith. If a man finds that his interpretation of Scripture is at variance with the teaching of the Church, he must humbly examine himself and ask whether his guide has not been his own private wishes rather than the Holy Spirit. It is Peter's insistence that Scripture does not consist of any man's private opinions but is the revelation of God to men through his Spirit; and that, therefore, its interpretation must not depend on any man's private opinions but must ever be guided by that same Spirit who is still specially operative within the Church. FALSE PROPHETS

That there should arise false prophets within the Church was something only to be expected, for in every generation false prophets had been responsible for leading God's people astray and for bringing disaster on the nation. It is worth while looking at the false prophets in the Old Testament story for their characteristics were recurring in the time of Peter and are still recurring today. (i) The false prophets were more interested in gaining popularity than in telling the truth. Their policy was to tell people what they wanted to hear. The false prophets said, "Peace, peace, when there is no peace" (Jeremiah 6:14). They saw visions of peace, when the Lord God was saying that there was no peace (Ezekiel 13:16). In the days of Jehosaphat, Zedekiah, the false prophet, donned his horns of iron and said that Israel would push the Syrians out of the way as he pushed with these horns; Micaiah the true prophet foretold disaster if Jehosaphat went to war. Of course, Zedekiah was popular and his message was accepted; but Jehoshaphat went forth to war with the Syrians and perished tragically (I Kings 22). In the days of Jeremiah, Hananiah prophesied the swift end of the power of Babylon, while Jeremiah prophesied the servitude of the nation to her; and again the prophet who told people what they wished to hear was the popular one (Jeremiah 28). Diogenes, the great cynic philosopher, spoke of the false teachers of his day whose method was to follow wherever the applause of the crowd led. One of the first characteristics of the false prophet is that he tells men what they want to hear and not the truth they need to hear. (ii) The false prophets were interested in personal gain. As Micah said, "Its priests teach for hire, and its prophets divine for money" (Micah 3:11). They teach for filthy lucre's sake (Titus I:11), and they identify godliness and gain, making their religion a money-making thing (I Timothy 6:5). We can see these exploiters at work in the early church. In The Didache, The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, which is what might be called the first service-order book, it is laid down that a prophet who asks for money or for a table to be spread in front of him, is a false prophet. "Traffickers in Christ" The Didache calls such men (The Didache 11). The false prophet is a covetous creature who regards men as dupes to be exploited for his own ends. (iii) The false prophets were dissolute in their personal life. Isaiah writes: "The priest and the prophet reel with strong drink; they are confused with wine" (Isaiah 28:7). Jeremiah says, "In the prophets of Jerusalem I have seen a horrible thing; they commit adultery and walk in lies; they strengthen the hands of evil-doers....They lead my people astray by their lies and their recklessness" (Jeremiah 23:14, 32). The false prophet in himself is a seduction to evil rather than an attraction to good. (iv) The false prophet was above all a man who led other men further away from God instead of closer to him. The prophet who invites the people: "Let us go after other gods," must be mercilessly destroyed (Deuteronomy), 13:1-5; 18:20). The false prophet takes men in the wrong direction. These were the characteristics of the false prophets in the ancient days and in Peter's time; and they are their characteristics still. THE SINS OF THE FALSE PROPHETS AND THEIR END In this verse Peter has certain things to say about these false prophets and their actions. (i) They insidiously introduce destructive heresies. The Greek for heresy is hairesis. It comes from the verb haireisthai, which means to choose; and originally it was a perfectly honourable word. It simply meant a line of belief and action which a man had chosen for himself. In the New Testament we read of the hairesis of the Sadducees, the Pharisees, and the Nazarenes (Acts 5:17; 15:5; 24:5). It was perfectly possible to speak of the hairesis of Plato and to mean nothing more than those who were Platonist in their thought. It was perfectly possible to speak of a group of doctors who practiced a certain method of treatment as a hairesis. But very soon in the Christian Church hairesis changed its complexion. In Paul's thought heresies and schisms go together as things to be condemned (I Corinthians 11:18, 19); haireseis (the plural form of the word) are part of the works of the flesh; a man that is a heretic is to be warned and even given a second chance, and then rejected (Titus 3:10). Why the change? The point is that before the coming of Jesus, who is the way, the truth, and the life, there was no such thing as definite, God-given truth. A man was presented with a number of alternatives any one of which he was perfectly free to choose to believe. But with the coming of Jesus, God's truth came to men and they had either to accept or to reject it. A heretic then became a man who believed what he wished to believe instead of accepting the truth of God which he ought to believe. What was happening in the case of Peter's people that certain self-styled prophets were insidiously persuading men to believe the things they wished to be true rather than the things which God had revealed to be true. They did not set themselves up as opponents of Christianity. Far from it. They set themselves up as the finest fruits of Christian thinking; and so it was gradually and subtly that people were being lured away from God's truth to other men's private opinions, which is what heresy is. (ii) These men denied the Lord who had bought them. This idea of Christ buying men for himself is one which runs through the whole New Testament. It comes from his own word that he had come to give his life a ransom for many (Mark 10:45). The idea was that men were slaves to sin and Jesus purchased them at the cost of his life for himself, and, therefore, for freedom. "You were bought with a price," says Paul (I Corinthians 7:23). "Christ redeemed us (bought us out) from the curse of the law" (Galatians 3:13). In the new song in the Revelation the hosts of heaven tell how Jesus Christ bought them with his blood out of every kindred and tongue and people and nation (Revelation 5:9). This clearly means two things. It means that the Christian by right of purchase belongs absolutely to Christ; and it means that a life which cost so much cannot be squandered on sin or on cheap things. The heretics in Peter's letter were denying the Lord who bought them. That could mean that they were saying that they did not know Christ; and it could mean that they were denying his authority. But it is not as simple as that; one might say that it is not as honest as that. We have seen that these men claimed to be Christians; more, they claimed to be the wisest and the most advanced of Christians. Let us take a human analogy. Suppose a man says that he loves his wife and yet is consistently unfaithful to her. By his acts of infidelity he denies, gives the lie to his words of love. Suppose a man protests eternal friendship to someone, and yet is consistently disloyal to him. His actions deny, give the lie to, his protestations of friendship. What these evil men, who were troubling Peter's people, were doing, was to say that they loved and served Christ, while the things they taught and did were a complete denial of him. (iii) The end of these evil men was destruction. They were insidiously introducing destructive heresies, but these heresies would in the end destroy themselves. There is no more certain way to ultimate condemnation than to teach another to sin. THE WORK OF FALSEHOOD

In this short passage we see four things about the false teachers and their teaching. (i) We see the cause of false teaching. It is evil ambition. The word is pleonexia; pleon means more and exia comes from the verb echein, which means to have. Pleonexia is the desire to possess more but it acquires a certain flavor. It is by no means always a sin to desire to possess more; there are many cases in which that is a perfectly honorable desire, as in the case of virtue, or knowledge, or skill. But pleonexia comes to mean the desire to possess that which a man has no right to desire, still less to take. So it can mean covetous desire for money and for other people's goods; lustful desire for someone's person; unholy ambition for prestige and power. False teaching comes from the desire to put its own ideas in the place of the truth of Jesus Christ; the false teacher is guilty of nothing less than of usurping the place of Christ. (ii) We see the method of false teaching. It is the use of cunningly forged arguments. Falsehood is easily resisted when it is presented as falsehood; it is when it is disguised as truth that it becomes menacing. There is only one touchstone. Any teacher's teaching must be tested by the words and presence of Jesus Christ himself. (iii) We see the effect of the false teaching. It was twofold. It encouraged men to take the way of blatant immorality. The word is aselgeia which describes the attitude of the man who is lost to shame and cares for the judgment of neither man nor God. We must remember what was at the back of this false teaching. It was perverting the grace of God into a justification for sin. The false teachers were telling men that grace was inexhaustible and that, therefore, they were free to sin as they liked for grace would forgive. This false teaching had a second effect. It brought Christianity into disrepute. In the early days, just as now, every Christian was a good or bad advertisement for Christianity and the Christian Church. It is Paul's accusation to the Jews that through them the name of God has been brought into disrepute (Romans 2:24). In the Pastoral Epistles the younger women are urged to behave with such modesty and chastity that the Church will never be brought into disrepute (Titus 2:5). Any teaching which produces a person who repels men from Christianity instead of attracting them to it is false teaching, and the work of those who are enemies of Christ. (iv) We see the ultimate end of false teaching and that is destruction. Sentence was passed on the false prophets long ago; the Old Testament pronounced their doom (Deuteronomy 13:1-5). It might look as if that sentence had become inoperative or was slumbering, but it was still valid, and the day would come when the false teachers would pay the terrible price of their falsehood. No man who leads another astray will ever escape his own judgment. THE FATE OF THE WICKED AND THE RESCUE OF THE RIGHTEOUS

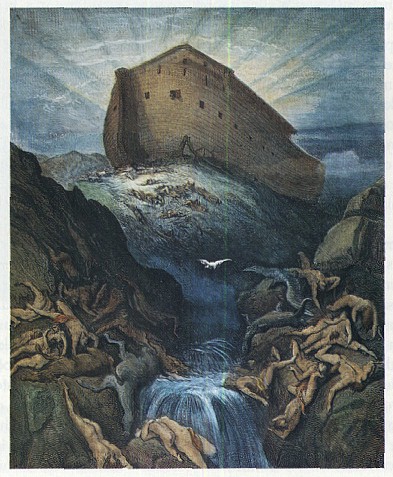

Here is a passage which for us combines undoubted power and equally undoubted obscurity. The white heat of its rhetorical intensity glows through it to this day; but it moves in allusions which would be terrifyingly effective to those who heard it for the first time, but which have become unfamiliar to us today. It cites three notorious examples of sin and its destruction; and in two of the cases it shows how, when sin was obliterated, righteousness was rescued and preserved by the mercy and the grace of God. Let us look at these examples one by one. 1. THE SIN OF THE ANGELS Before we retell the story which lies behind this in Jewish legend, there are two separate words at which we must look. Peter says that God condemned the sinning angels to the lowest depths of hell. Literally the Greek says that God condemned the angels to Tartarus (tartaroun). Tartarus was not a Hebrew conception but Greek. In Greek mythology Tartarus was the lowest hell; it was as far beneath Hades as the heaven is high above the earth. In particular it was the place into which there had been cast the Titans who had rebelled against Zeus, the Father of gods and men. The second word is that which speaks of the pits of darkness. Here there is a doubt. There are two Greek words, both rather uncommon, which are confused in this passage. One is siros or seiros which originally meant a great earthenware jar for the storing of grain. Then it came to mean the great underground pits in which grain was stored and which served as granaries. Siros has come into English via Provençal in the form of silo, which still describes the towers in which grain is stored. Still later the word went on to mean a pit in which a wolf or other wild animal was trapped. If we think that this is the word which Peter uses, and according to the best manuscripts it is, it will mean that the wicked angels were cast into great subterranean pits and kept there in darkness and in punishment. This well suits the idea of a Tartarus beneath the lowest depths of Hades. But there is a very similar word seira, which means a chain. This is the word which the Authorized Version translates when it speaks of chains of darkness (verse 4). The Greek manuscripts of Second Peter vary between seiroi, pits, and seirai, chains. But the better manuscripts have seiroi, and pits of darkness makes better sense than chains of darkness; so we may take seiros as right, and assume that here the Authorized Version is in error. The story of the fall of the angels is one which rooted itself deeply in Hebrew thought and which underwent much development as the years went on. The original story is in Genesis 6:1-5. There the angels are called the sons of God, as they commonly are in the Old Testament. In Job, the sons of God come to present themselves before the Lord, and Satan comes amongst them (Job 1:6; cp. 2:1 ; 38:7). The Psalmist speaks of the sons of gods (Psalm 89:6). These angels came to earth and seduced mortal women. The result of this lustful union was the race of giants; and through them wickedness came upon the earth. Clearly this is an old, old story belonging to the childhood of the race. This story was much developed in the Book of Enoch, and it is from it that Peter is drawing his allusions, for in his day that was a book which everyone would know. In Enoch the angels are called The Watchers. Their leader in rebellion was Semjaza or Azazel. At his instigation they descended to Mount Hermon in the days of Jared, the father of Enoch. They took mortal wives and instructed them in magic and in arts which gave them power. They produced the race of the giants, and the giants produced the Nephilim, the giants who inhabited the land of Canaan and of whom the people were afraid (Numbers 13:33). These giants became cannibals and were guilty of every kind of lust and crime, and especially of insolent arrogance to God and man. The apocryphal literature has many references to them and their pride. Wisdom (14:6) tells how the proud giants perished. Ecclesiasticus (16:7) tells how the ancient giants fell away in the strength of their foolishness. They had no wisdom and they perished in their folly (Baruch 3:26-28). Josephus says that they were arrogant and contemptuous of all that was good and trusted in their own strength (Antiquities 1.3.1). Job says that God charged his angels with folly (Job 4:18). This old story makes a strange and fleeting appearance in the letters of Paul. In 1 Corinthians 11:10 Paul says that women must have their hair covered in the Church because of the angels. Behind that strange saying ties the old belief that it was the loveliness of the long hair of the women of the olden times which moved the angels to desire; and Paul wishes to see that the angels are not tempted again. In the end even men complained of the sorrow and misery brought into the world by these giants through the sin of the angels. The result was that God sent out his archangels. Raphael bound Azazel hand and foot and shut him up in darkness; Gabriel slew the giants; and the Watchers, the sinning angels, were shut up in the abysses of darkness under the mountains for seventy generations and then confined for ever in everlasting fire. Here is the story which is in Peter's mind; and which his readers well knew. The angels had sinned and God had sent his destruction, and they were shut up for ever in the pits of darkness and the depths of hell. That is what happens to rebellious sin. The story does not stop there; and it reappears in another of its forms in this passage of Second Peter. In verse 10 Peter speaks of those who live lives dominated by the polluting lusts of the flesh and who despise the celestial powers. The word is kuriotes, which is the name of one of the ranks of angels. They speak evil of the angelic glories. The word is doxai, which also is a word for one of the ranks of angels. They slander the angels and bring them into disrepute. Here is where the second turn of the story comes in. Obviously this story of the angels is very primitive and, as time went on, it became rather an awkward and embarrassing story because of its ascription of lust to angels. So in later Jewish and Christian thought two lines of thought developed. First, it was denied that the story involved angels at all. The sons of God were said to be good men who were the descendants of Seth, and the daughters of men were said to be evil women who were the daughters of Cain and corrupted the good men. There is no scriptural evidence for this distinction and this way of escape. Second, the whole story was allegorized. It was claimed, for instance by Philo, that it was never meant to be taken literally and described the fall of the human soul under the attack of the seductions of lustful pleasures. Augustine declared that no man could take this story literally and talk of the angels like that. Cyril of Alexandria said that it could not be taken literally, for did not Jesus say that in the after-life men would be like angels and there would be no marrying or giving in marriage (Matthew 22:30)? Chrysostom said that, if the story was taken literally, it was nothing short of blasphemy. And Cyril went on to say that the story was nothing other than an incentive to sin, if it was taken as literally true. It is clear that men began to see that this was indeed a dangerous story. Here we get our clue as to what Peter means when he speaks of men who despise the celestial powers and bring the angelic glories into disrepute by speaking slanderously of them. The men whom Peter was opposing were turning their religion into an excuse for blatant immorality. Cyril of Alexandria makes it clear that in his day the story could be used as an incentive to sin. Most probably what was happening was that the wicked men of Peter's time were citing the example of the angels as a justification for their own sin. They were saying, "If angels came from heaven and took mortal women, why should not we?" They were making the conduct of the angels an excuse for their own sin. We have to go still further with this passage. In verse 11 it finishes very obscurely. It says that angels who are greater in strength and in power do not bring a slanderous charge against them in the presence of God. Once again Peter is speaking allusively, in a way that would be clear enough to the people of his day but which is obscure to us. His reference may be to either of two stories. (a) He may be referring to the story to which Jude refers in Jude 9; that the archangel Michael was entrusted with the burying of the body of Moses. Satan claimed the body on the grounds that all matter belonged to him and that once Moses, had murdered an Egyptian. Michael did not bring a railing charge against Satan; all he said was: "The Lord rebuke you." The point is that even an angel so great as Michael would not, bring an evil charge against an angel so dark as Satan. He left the matter to God. If Michael refrained from slander of an evil angel, how can men bring slanderous charges against the angels of God? (b) He may be referring to a further development of Enoch story. Enoch tells that when the conduct of the giants on earth became intolerable, men made their complaint to the archangels Michael, Uriel, Gabriel and Raphael. The archangels took this complaint to God; but they did not rail against the evil angels who were responsible for it all; they simply took the story to God, for him to deal with (Enoch 9). As far as we can see today, the situation behind Peter's allusions is that the wicked men who were the slaves of lust claimed that the angels were their examples and their justification and so slandered them; Peter reminds them that not even archangels dared slander other angels and demands how men can dare to do so. This is a strange and difficult passage; but the meaning is clear. Even angels, when they sinned, were punished. How much more shall men be punished? Angels could not rebel against God and escape the consequences. How shall men escape? And men need not seek to put the blame on others, not even on angels; nothing but their own rebelliousness is responsible for their sin. 2. THE MEN OF THE FLOOD AND THE RESCUE OF NOAH The second illustration of the destruction of wickedness which Peter chooses may be said to lead on from the first. The sin introduced into the world by the sinning angels led to that intolerable sin which ended in the destruction by the deluge (Genesis 6:5). In the midst of this destruction God did not forget those who had clung to him, Noah was saved together with seven others, his wife, his sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, and their wives. In Jewish tradition Noah acquired a very special place. Not only was he regarded as the one man who had been saved; but also as the preacher who had done his best to turn men from the evil of their ways. Josephus says, "Many angels of God lay with women and begat sons, who were violent and who despised all good, on account of their reliance on their own strength. But Noah displeased and distressed at their behaviour, tried to induce them to alter their dispositions and conduct for the better" (Antiquities 1.3.1). Attention in this passage is concentrated not so much on the people who were destroyed as on the man who was saved. Noah is offered as the type of man who, amidst the destruction of the wicked, receives the salvation of God. His outstanding qualities were two. (i) In the midst of a sinning generation he remained faithful to God. Later Paul was to urge his people to be not conformed to the world but transformed from it (Romans 12:2). It may well be said that often the most dangerous sin of all is conformity. To be the same as others is always easy; to be different is always difficult. But from the days of Noah until now he who would be the servant of God must be prepared to be different from the world. (ii) The later legends pick out another characteristic of Noah. He was the preacher of righteousness. The word for preacher used here is kerux, which literally means a herald. Epicletus called the philosopher the kerux of the gods. The preacher is the man who brings to men an announcement from God. Here is something of very considerable significance. The good man is concerned not only with the saving of his own soul but just as much with the saving of the souls of others. He does not, in order to preserve his own purity live apart from men. He is concerned to bring God's message to them. A man ought never to keep to himself the grace which he has received. It is always his duty to bring light to those who sit in darkness, guidance to the wanderer and warning to those who are going astray. 3. THE DESTRUCTION OF SODOM AND GOMORRAH AND THE RESCUE OF LOT The third example is the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and the rescue of Lot. The terrible and dramatic story is told in Genesis 18 and 19. It begins with Abraham's plea that God should not destroy the righteous with the guilty and his request that, if even ten just men are found in these cities, they may be spared (Genesis 18:16-33). Then follows one of the grimmest tales in the Old Testament. The angelic visitors came to Lot and he persuaded them to stay with him; but his house was surrounded by the men of Sodom demanding that these strangers might be brought out for them to use for their unnatural lust (Genesis 19:1-11). By that terrible deed--at once the abuse of hospitality, the insulting of angels and the raging of unnatural lust--the doom of the cities was sealed. As the destruction of heaven came upon them Lot and his family were saved, except his wife, who lingered and looked back and turned into a pillar of salt (Genesis 19:12-26). "So it was that, when God destroyed the cities of the valley, God remembered Abraham, and sent Lot out of the midst of the overthrow, when he overthrew the cities in which Lot dwelt" (Genesis 19:29). Here again is the story of the destruction of sin and the rescue of righteousness. As in Noah, we see in Lot the characteristics of the righteous man. (i) Lot lived in the midst of evil, and the very sight of it was a constant distress to him. Moffatt reminds us of the saying of Newman: "Our great security against sin lies in being shocked at it." Here is something very significant. It often happens that, when evils first emerge, people are shocked at them; but, as time goes on, they cease to be shocked at them and accept them as a matter of course. There are many things at which we ought to be shocked. In our own generation there are the problems of prostitution and promiscuity, drunkenness and drugs, the extraordinary gambling fever which has the country in its grip, the breakdown of the marriage bond, violence, vandalism and crime, death upon the roads, still-existing slum conditions and many others. In many cases the tragedy is that these things have ceased to shock and are accepted in a matter-of-fact style as part of the normal order of things. For the good of the world and of our own souls, we must keep alive the sensitiveness which is shocked by sin. (ii) Lot lived in the midst of evil, and yet he escaped its taint. Amidst the sin of Sodom he remained true to God. If a man will remember it, he has in the grace of God an antiseptic which will preserve him from the infection of sin. No man need be the slave of the environment in which he happens to find himself. (iii) When the worst came to the worst, Lot was willing to make a clean break with his environment. He was prepared, however much he did not want to do so, to leave it for ever. It was because his wife was not prepared to make the clean break that she perished. There is a strange verse in the Old Testament story. It says that, when Lot lingered, the angelic messengers took hold of his hand (Genesis 19:16). There are times when the influence of heaven tries to force us out of some evil situation. It may come to any man to have to make the choice between security and the new start; and there are times when a man can save his soul only by breaking clean away from his present situation and beginning all over again. It was in doing just this that Lot found his salvation; and it was in failing to do just this that his wife lost hers. THE PICTURE OF THE EVIL MAN Verses 9-11 give us a picture of the evil man. Peter with a few swift, vivid strokes of the Pen paints the outstanding characteristics of him who may properly be called the bad man. (i) He is the desire-dominated man. His life is dominated, by the lusts of the flesh. Such a man is guilty of two sins. (a) Every man has two sides to his nature. He has a physical side; he has instincts, passions and impulses which he shares with the animal creation. These instincts are good if they are kept in their proper place. They are even necessary for the preservation of individual life and the continuation of the race. The word temperament literally means a mixture. The picture behind it is that human nature consists of a large variety of ingredients all mixed together. It is clear that the efficacy of any mixture depends on each ingredient being there in its proper proportion. Wherever there is either excess or defect the mixture is not what it ought to be. Man has a physical nature and also a spiritual nature; and manhood depends on a correct mixture of the two. The desire-dominated man has allowed his animal nature to usurp a place it should not have; he has allowed the ingredients to get out of proportion and the recipe for manhood has gone wrong. (b) There is a reason for this loss of proportion--selfishness. The root evil of the lust-dominated life is that it proceeds on the assumption that nothing matters but the gratification of its own desires and the expression of its own feelings. It has ceased to have any respect or care for others. Selfishness and desire go hand in hand. The bad man is he who has allowed one side of his nature a far greater place than it ought to have and who has done so because he is essentially selfish. (ii) He is the audacious man. The Greek is tolmetes, from the verb tolman, to dare. There are two kinds of daring. There is the daring which is a noble thing, the mark of true courage. There is the daring which is an evil thing, the shameless performance of things which are an affront to decency and right. As the character in Shakespeare had it: "I dare do all becomes a man. Who dares do more is none." The bad man is he who has the audacity to defy the will of God as it is known to him. (iii) He is the self-willed man. Self-willed is not really an adequate translation. The Greek is authades, derived from autos, self, and hadon, pleasing, and used of a man who had no idea of anything other than pleasing himself. In it there is always the element of obstinacy. If a man is authades, no logic, nor common sense, nor appeal, nor sense of decency will keep him from doing what he wants to do. As R. C. Trench says, "Thus obstinately maintaining his own opinion, or asserting his own rights, he is reckless of the rights, opinions and interests of others." The man who is authades is stubbornly and arrogantly and even brutally determined on his own way. The bad man is he who has no regard for either human appeal or divine guidance. (iv) He is the man who is contemptuous of the angels. We have already seen how this goes back to allusions in Hebrew tradition which are obscure to us. But it has a wider meaning The bad man insists on living in one world. To him the spiritual world does not exist and he never hears the voice from beyond. He is of the earth earthy. He has forgotten that there is a heaven and is blind and deaf when the sights and sounds of heaven break through to him. DELUDING SELF AND DELUDING OTHERS

Peter launches out into a long passage of magnificent invective. Through it glows the fiery heat of flaming moral indignation. The evil men are like brute beasts, slaves of their animal instincts. But a beast is born only for capture and death, says Peter; it has no other destiny. Even so, there is something self-destroying in fleshly pleasure. To make such pleasure the be-all and the end-all of life is a suicidal policy and in the end even the pleasure is lost. The point Peter is making Is this, and it is eternally valid-if a man dedicates himself to these fleshly pleasures, in the end he so ruins himself in bodily health and in spiritual and mental character, that he cannot enjoy even them. The glutton destroys his appetite in the end, the drunkard his health, the sensualist his body, the self-indulgent his character and peace of mind. These men regard daylight debauchery, dissipated reveling, abandoned carousing as pleasure. They are blots on the Christian fellowship; they are like the blemishes on an animal, which make it unfit to be offered to God. Once again we must note that what Peter is saying is not only religious truth but also sound common sense. The pleasures of the body are demonstrably subject to the law of diminishing returns. In themselves they lose their thrill, so that as time goes on takes more and more of them to satisfy. The luxury must become ever more luxurious; the wine must flow ever more freely; everything must be done to make the thrill sharper and more intense. Further, a man becomes less and less able to enjoy these pleasures. He has given himself to a life that has no future and to pleasure which ends in pain. Peter goes on. In verse 14 he uses an extraordinary phrase which, strictly, will not translate into English at all. We have translated it: "They have eyes full of adultery." The Greek literally is: "They have eyes which are full of an adulteress." Most probably the meaning is they see a possible adulteress in every woman, wondering how she can be persuaded to gratify their lusts. "The hand and the eye," said the Jewish teachers, "are the brokers of sin." As Jesus said, such people look in order to lust (Matthew 5:28). They have come to such a stage that they cannot look on anyone without lust's calculation. As Peter speaks of this, there is a terrible deliberateness about it. They have hearts trained in unbridled ambition for the things they have no right to have. We have taken a whole phrase to translate the one word pleonexia which means the desire to have more of the things which a man has no right even to desire, let alone have. The picture is a terrible one. The word used for trained is used for an athlete exercising himself for the games. These people have actually trained their minds to concentrate on nothing but the forbidden desire. They have deliberately fought with conscience until they have destroyed it; they have deliberately struggled with their finer feelings until they have strangled them. There remains in this passage one further charge. It would be bad if these people deluded only themselves; it is worse that they delude others. They entrap souls not firmly founded in the faith. The word used for to entrap is deleazein, which means to catch with a bait. A man becomes really bad when he sets out to make others as bad as himself. The hymn has it:

Every man must bear the responsibility for his own sins, but to add to that the responsibility for the sins of others is to carry an intolerable burden. ON THE WRONG ROAD

Peter likens the evil men of his time to the prophet Balaam. In the popular Jewish mind Balaam had come to stand as the type of all false prophets. His story is told in Numbers 22 to 24. Balak, King of Moab, was alarmed at the steady and apparently irresistible advance of the Israelites. In an attempt to check it he sent for Balaam to come and curse the Israelites for him, offering him great rewards. To the end of the day Balaam refused to curse the Israelites, but his covetous heart longed after the rich rewards which Balak was offering. At Balak's renewed request Balaam played with fire enough to agree to meet him. On the way his ass stopped, because it saw the angel of the Lord standing in its path, and rebuked Balaam. It is true that Balaam did not succumb to Balak's bribes, but if ever a man wanted to accept a bribe, that man was he. In Numbers 25 there follows another story. It tells how the Israelites were seduced into the worship of Baal and into lustful alliances with Moabite women. Jewish belief was that Balaam was responsible for leading the children of Israel astray; and when the Israelites entered into possession of the land, "Balaam the son of Beor they slew with the sword" (Numbers 31:8). In view of all this Balaam became increasingly the type of the false prophet. He had two characteristics which were repeated in the evil men of Peter's day. (i) Balaam was covetous. As the Numbers story unfolds we can see his fingers itching to get at the gold of Balak. True, he did not take it; but the desire was there. The evil men of Peter's day were covetous; out for what they could get and ready to exploit their membership of the Church for gain. (ii) Balaam taught Israel to sin. He led the people out of the straight and into the crooked way. He persuaded them to forget their promises to God. The evil men of Peter's day were seducing Christians from the Christian way and causing them to break the pledges of loyalty they had given to Jesus Christ. The man who loves gain and who lures others to evil forever stands condemned. THE PERILS OF RELAPSE These people are waterless springs, mists driven by a squall of wind--and the gloom of darkness is reserved for them. With talk at once arrogant and futile, they ensnare by appeals to shameless, sensual passions those who are only just escaping from the company of those who live in error, promising them freedom, while they themselves are the slaves of moral corruption; for a man is in a state of slavery to that which has reduced him to helplessness. (2 Peter 2:17-22) If they have escaped the pollution of the world by the knowledge of the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, and if they allow themselves again to become involved in these things and to be reduced to moral helplessness by them, the last state is for them worse than the first. It would be better for them not to have known the way of righteousness than to have known it and then to turn back from the holy commandment which was handed down to them. In them the truth of the proverb is plain to see: "A dog returns to his own vomit" and "The sow which has been washed returns to rolling in the mud." Peter is still rolling out his tremendous denunciation of the evil men. They flatter only to deceive. They are like wells with no water and like mists blown past by a squall of wind. Think of a traveler in the desert being told that ahead lies a spring where he can quench his thirst and then arriving at that spring to find it dried up and useless. Think of the husbandman praying for rain for his parched crops and then seeing the cloud that promised rain blown uselessly by. As Bigg has it: "A teacher without knowledge is like a well without water." These men are like Milton's shepherds whose "hungry sheep look up and are not fed." They promise a gospel and in the end have nothing to offer the thirsty soul. Their teaching is a combination of arrogance and futility. Christian liberty always carries danger. Paul tells his people that they have indeed been called to liberty but that they must not use it for an occasion to the flesh (Galatians 5:13). Peter tells his people that indeed they are free but they must not use their freedom as a cloak of maliciousness (I Peter 2:16). These false teachers offered freedom, but it was freedom to sin as much as a man liked. They appealed not to the best but to the worst in a man. Peter is quite clear that they did this because they were slaves to their own lusts. Seneca said, "To be enslaved to oneself is the heaviest of all servitudes." Persius spoke to the lustful debauchees of his day of "the masters that grow up within that sickly breast of yours." These teachers were offering liberty when they themselves were slaves, and the liberty they were offering was the liberty to become slaves of lust. Their message was arrogant because it was the contradiction of the message of Christ; it was futile because he who followed it would find himself a slave. Here again in the background is the fundamental heresy which makes grace a justification for sin instead of a power and a summons to nobility. If they have once known the real way of Christ and have relapsed into this, their case is even worse. They are like the man in the parable whose last state was worse than his first (Matthew 12:45; Luke 11:26). If a man has never known the right way, he cannot be condemned for not following it. But, if he has known it and then deliberately taken the other way, he sins against the light; and it were better for him that he had never known the truth, for his knowledge of the truth has become his condemnation. A man should never forget the responsibility which knowledge brings. Peter ends with contempt. These evil men are like dogs who return to their vomit (Proverbs 26:11) or like a sow which has been scrubbed and then goes back to rolling in the mud. They have seen Christ but are so morally degraded by their own choice that they prefer to wallow in the depths of sin rather than to climb the heights of virtue. It is a dreadful warning that a man can make himself such that in the end the tentacles of sin are inextricably around him and virtue for him has lost its beauty. THE PRINCIPLES OF PREACHING Beloved, this is now the second letter that I have written to you, and my object in both of them is to rouse by reminder your pure mind to remember the words spoken by the prophets in former times, and the commandment of the Lord and Savior which was brought to you by your apostles. (2 Peter 3:1, 2) In this passage we see clearly displayed the principles of preaching which Peter observed. (i) He believed in the value of repetition. He knows that it is necessary for a thing to be said over and over again if it is to penetrate the mind. When Paul was writing to the Philippians, he said that to repeat the same thing over and over again was not a weariness to him, and for them it was the only safe way (Philippians 3:1). It is by continued repetition that the rudiments of knowledge are settled in the mind of the child. There is something of significance here. It may well be that often we are too desirous of novelty, too eager to say new things, when what is needed is a repetition of the eternal truths which men so quickly forget and whose significance they so often refuse to see. There are certain foods of which a man does not get tired; necessary for his daily sustenance they are set before him every day. We speak about a man's daily bread. And there are certain great Christian truths which have to be repeated again and again and which must never be pushed into the background in the desire for novelty. (ii) He believed in the need for reminder. Again and again the New Testament makes it clear that preaching and teaching are so often not the introducing of new truth but the reminding of a man of what he already knows. Moffatt quotes a saying of Dr. Johnson: "it is not sufficiently considered that men more frequently require to be reminded than informed." The Greeks spoke of "time which wipes all things out," as if the human mind were a slate and time a sponge which passes across it with a certain erasing quality. We are so often in the position of men whose need is not so much to be taught as to be reminded of what we already know. (iii) He believed in the value of a compliment. It is his intention to rouse their pure mind. The word he uses for pure is eilikrines, which may have either of two meanings. It may mean that which is sifted until there is no admixture of chaff left; or it may mean that which is so flawless that it may be held up to the light of the sun. Plato uses this same phrase - eilikrines dianoia-in the sense of pure reason, reason which is unaffected by the seductive influence of the senses. By using this phrase Peter appeals to his people as having minds uncontaminated by heresy. It Is as if he said to them: "You really are fine people-if you would only remember it." The approach of the preacher should so often be that his hearers are not wretched creatures who deserve to be damned but splendid creatures who must be saved. They are not so much like rubbish fit to be burned as like jewels to be rescued from the mud into which they have fallen. Donald Hankey tells of "the beloved captain" whose men would follow him anywhere. He looked at them and they looked at him, and they were filled with the determination to be what he believed them to be. We always get further with people when we believe in them than when we despise them. (iv) He believed in the unit), of Scripture. As he saw it there was a pattern in Scripture; and the Bible was a book centered in Christ. The Old Testament foretells Christ; the gospels tell of Jesus the Christ; and the apostles bring the message of that Christ to men. THE DENIAL OF THE SECOND COMING

The characteristic of the heretics which worried Peter most of all was their denial of the Second Coming of Jesus. Literally, their question was: "Where is the promise of his Coming?" That was a form of Hebrew expression which implied that the thing asked about did not exist at all. "Where is the God of justice?" asked the evil men of Malachi's day (Malachi 2:17). "Where is your God?" the heathen demanded of the Psalmist (Psalm 42:3; 79:10). "Where is the word of the Lord?" his enemies asked Jeremiah (Jeremiah 17:15). In every case the implication of the question is that the thing or the person asked about does not exist. The heretics of Peter's day were denying that Jesus Christ would ever come again. It will be best here at the beginning to summarize their argument and Peter's answer to it. The argument of Peter's opponents was twofold (verse 4). "What has happened," they demanded, "to the promise of the Second Coming?" Their first argument was that the promise had been so long delayed that it was safe to take it that it would never be fulfilled. Their second assertion was that their fathers had died and the world was going on precisely as it always did. Their argument was that this was characteristically a stable universe and convulsive upheavals like the Second Coming did not happen in such a universe. Peter's response is also twofold. He deals with the second argument first (verses 5-7). His argument is that, in fact, this is not a stable universe, that once it was destroyed by water in the time of the Flood and that a second destruction, this time by fire, is on the way. The second part of his reply is in verses 8 and 9. His opponents speak of a delay so long that they can safely assume that the Second Coming is not going to happen at all. Peter's is a double answer. (a) We must see time as God sees it. With him a day is as a thousand years and a thousand years as a day. "God does not pay every Friday night." (b) In any event God's apparent slowness to act is not dilatoriness. It is, in fact, mercy. He holds his hand in order to give sinning men another chance to repent and find salvation. Peter goes on to his conclusion (verse 10). The Second Coming is on the way and it will come with a sudden terror and destruction which will dissolve the universe in melting heat. Finally comes his practical demand in face of all this. If we are living in a universe on which Jesus Christ is going to descend and which is hastening towards the destruction of the wicked, surely it behooves us to live in holiness so that we may be spared when the terrible day does come. The Second Coming is used as a tremendous motive for moral amendment so that a man may prepare himself to meet his God. Such, then, is the general scheme of this chapter and now we look at it section by section. DESTRUCTION BY FLOOD

Peter's first argument is that the world is not eternally stable. The point he is making is that the ancient world was destroyed by water, just as the present world is going to be destroyed by fire. The detail of this passage is, however, difficult. He says that the earth was composed out of water and through water. According to the Genesis story in the beginning there was a kind of watery chaos. "The Spirit of God moved over the face of the waters. God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters" (Genesis I:2, 6). Out of this watery chaos the world was formed. Further, it is through water that the world is sustained, because life is sustained by the rain which comes down from the skies. What Peter means is that the world was created out of water and is sustained by water; and it was through this same element that the ancient world was destroyed. Further to clarify this passage we have to note that the flood legend developed. As so often in Second Peter and Jude the picture behind this comes not directly from the Old Testament but from the Book of Enoch. In Enoch 83:3-5 Enoch has a vision: "I saw in a vision how the heaven collapsed and fell to the earth, and, where it fell to the earth, I saw how the earth was swallowed up in a great abyss." In the later stories the flood involved not only the obliteration of sinners but the total destruction of heaven and earth. So the warning which Peter is giving may be put like this: "You say that as things are, so they have ever been and so they ever will be. You build your hopes on the idea that this is an unchanging universe. You are wrong, for the ancient world was formed out of water and was sustained by water, and it perished in the flood." We may say that this is only an old legend more than half buried in the antiquities of the past. But we cannot say that a passage like this has no significance for us. When we strip away the old Jewish legend and its later development, we are still left with this permanent truth that the man who will read history with open eyes can see within it the moral law at work and God's dealings with men. Froude, the great historian, said that history is a voice sounding across the centuries that in the end it is always ill with the wicked and well with the good. When Oliver Cromwell was arranging his son Richard's education, he said, "I would have him know a little history." In fact, the lesson of history is that there is a moral order in the universe and that he who defies it does so at his peril. DESTRUCTION BY FIRE

It is Peter's conviction that, as the ancient world was destroyed by water, the present world will be destroyed by fire. He says that that is stated "by the same word." What he means is that the Old Testament tells of the flood in the past and warns of the destruction by fire in the future. There are many passages in the prophets which he would take quite literally and which must have been in his mind. Joel foresaw a time when God would show blood, and fire, and pillars of smoke (Joel 2:30). The Psalmist has a picture in which, when God comes, a devouring fire shall precede him (Psalm 50:3). Isaiah speaks of a flame of devouring fire (Isaiah 29:6; 30:30). The Lord will come with fire; by fire and by his sword will the Lord plead with all flesh (Isaiah 66:15,16). Nahum has it that the hills melt and the earth is burned at his presence; his fury is poured out like fire (Nahum 1:5, 6). In the picture of Malachi the day of the Lord shall burn as an oven (Malachi 4:1). If the old pictures are taken literally, Peter has plenty of material for his prophecy. The Stoics also had a doctrine of the destruction of the world by fire; but it was a grim thing. They held that the universe completed a cycle; that it was consumed in flames; and that everything then started all over again, exactly as it was. They had the strange idea that at the end of the cycle the planets were in exactly the same position as when the world began. "This produces the conflagration and destruction of everything which exists," says Chrysippus. He goes on: "Then again the universe is restored anew in a precisely similar arrangement as before ... Socrates and Plato and each individual man will live again, with the same friends and fellow-citizens. They will go through the same experiences and the same activities. Every city and village and field will be restored, just as it was. And this restoration of the universe takes place, not once, but over and over again--indeed to all eternity without end. For there will never be any new thing other than that which has been before, but everything is repeated down to the minutest detail." History as an eternal tread-mill, the unceasing recurrence of the sins, the sorrows and the mistakes of men--that is one of the grimmest views of history that the mind of man has ever conceived. It must always be remembered that, as the Jewish prophets saw it, and as Peter saw it, this world will be destroyed with the conflagration of God but the result will not be obliteration and the grim repetition of what has been before; the result will be a new heaven and a new earth. For the biblical view of the world there is something beyond destruction; there is the new creation of God. The worst that the prophet can conceive is not the death agony of the old world so much as the birth pangs of the new. THE MERCY OF GOD'S DELAY

There are in this passage three great truths on which to nourish the mind and rest the heart. (i) Time is not the same to God as it is to man. As the Psalmist had it: "A thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past, or as a watch in the night" (Psalm 90:4). When we think of the world's hundreds of thousands of years of existence, it is easy to feel dwarfed into insignificance; when we think of the slowness of human progress, it is easy to become discouraged into pessimism. There is comfort in the thought of a God who has all eternity to work in. It is only against the background of eternity that things appear in their true proportions and assume their real value. (ii) We can also see from this passage that time is always to be regarded as an opportunity. As Peter saw it, the years God gave the world were a further opportunity for men to repent and turn to him. Every day which comes to us is a gift of mercy. It is an opportunity to develop ourselves; to render so service to our fellow-men; to take one step nearer to God. (iii) Finally, there is another echo of a truth which so often lies in the background of New Testament thought. God, says Peter, does not wish any to perish. God, says Paul, has shut them all up together in unbelief, that he might have mercy on all (Romans 11:32). Timothy in a tremendous phrase speaks of God who will have all men to be saved (I Timothy 2:4). Ezekiel hears God ask: "Have I any pleasure in the death of the wicked, and not rather that he should return from his way and live?" (Ezekiel 18:23). Ever and again there shines in Scripture the glint of the larger hope. We are not forbidden to believe that somehow and some time the God who loves the world will bring the whole world to himself. THE DREADFUL DAY

It inevitably happens that a man has to speak and think in the terms which he knows. That is what Peter is doing here. He is speaking of the New Testament doctrine of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, but he is describing it in terms of the Old Testament doctrine of the Day of the Lord. The Day of the Lord is a conception which runs all through the prophetic books of the Old Testament. The Jews saw time in terms of two ages- this present age, which is wholly bad and past remedy; and the age to come, which is the golden age of God. How was the one to turn into the other? The change could not come about by human effort or by a process of development, for the world was on the way to destruction. As the Jews saw it, there was only one way in which the change could happen; it must be by the direct intervention of God. The time of that intervention they called the Day of the Lord. It was to come without warning. It was to be a time when the universe was shaken to its foundations. It was to be a time when the judgment and obliteration of sinners would come to pass and, therefore, it would be a time of terror. "Behold the Day of the Lord comes, cruel with wrath and fierce anger, to make the earth a desolation and to destroy its sinners from it" (Isaiah 13:9). "The Day of the Lord is coming, it is near, a day of darkness and of gloom, a day of clouds and of thick darkness" (Joel 2:1, 2). "A day of wrath is that day, a day of distress and anguish, a day of ruin and devastation, a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness" (Zephaniah 1:14-18). "The sun shall be turned to darkness and the moon to blood, before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes" (Joel 2:30, 3 1). "The stars of the heaven and their constellations shall not give their light; the sun will be dark at its rising and the moon will not shed its light.... Therefore I will make the heavens tremble, and the earth will be shaken out of its place, at the wrath of the Lord of hosts in the day of his fierce anger" (Isaiah 13:10-13). What Peter and many of the New Testament writers did was to identify the Old Testament pictures of the Day of the Lord with the New Testament conception of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. Peter's picture here of the Second Coming of Jesus is drawn in terms of the Old Testament picture of the Day of the Lord. He uses one very vivid phrase. He says that the heavens will pass away with a crackling roar (roizedon). That word is used for the whirring of a bird's wings in the air, for the sound a spear makes as it hurtles through the air, for the crackling of the flames of a forest fire. We need not take these pictures with crude literalism. It is enough to note that Peter sees the Second Coming as a time of terror for those who are the enemies of Christ. One thing has to be held in the memory. The whole conception of the Second Coming is full of difficulty. But this is sure--there comes a day when God breaks into every life, for there comes a day when we must die; and for that day we must be prepared. We may say what we will about the Coming of Christ as a future event; we may feel it is a doctrine we have to lay on one side; but we cannot escape from the certainty of the entry of God into our own experience. THE MORAL DYNAMIC

The one thing in which Peter is supremely interested is the moral dynamic of the Second Coming. If these things are going to happen and the world is hastening to judgment, obviously a man must live a life of piety and of holiness. If there are to be a new heaven and a new earth and if that heaven and earth are to be the home of righteousness, obviously a man must seek with all his mind and heart and soul and strength to be fit to be a dweller in that new world. To Peter, as Moffatt puts it, "it was impossible to give up the hope of the advent without ethical deterioration." Peter was right. If there is nothing in the nature of a Second Coming, nothing in the nature of a goal to which the whole creation moves, then life is going nowhere. That, in fact, was the heathen position. If there is no goal, either for the world or for the individual life, other than extinction, certain attitudes to life become well-nigh inevitable. These attitudes emerge in heathen epitaphs. (i) If there is nothing to come, a man may well decide to make what he can of the pleasures of this world. So we come on an epitaph like this: "I was nothing I am nothing. So thou who art still alive, eat, drink, and be merry." (ii) If there is nothing to live for, a man may well be utterly indifferent. Nothing matters much if the end of everything is extinction, in which a man will not even be aware that he is extinguished. So we come on such an epitaph as this: "Once I had no existence; now I have none. I am not aware of it. It does not concern me." (iii) If there is nothing to live for but extinction and the world is going nowhere, there can enter into life a kind of lostness. Man ceases to be in any sense a pilgrim for there is nowhere to which he can make pilgrimage. He must simply drift in a kind of lostness, coming from nowhere and on the way to nowhere. So we come on an epigram like that of Callimachus. "Charidas, what is below?" "Deep darkness." "But what of the paths upward?" "All a lie." "And Pluto?" (The God of the underworld). "Mere talk." "Then we're lost." Even the heathen found a certain almost intolerable quality in a life without a goal. When we have stripped the doctrine of the Second Coming of all its temporary and local imagery, the tremendous truth it conserves is that life is going somewhere-and without that conviction there is nothing to live for. HASTENING THE DAY There is in this passage still another great conception. Peter speaks of the Christian as not only eagerly awaiting the Coming of Christ but as actually hastening it on. The New Testament tells us certain ways in which this may be done. (i) It may be done by prayer. Jesus taught us to pray: "Thy Kingdom come" (Matthew 6:10). The earnest prayer of the Christian heart hastens the coming of the King. If in no other way, it does so in this-that he who prays opens his own heart for the entry of the King. (ii) It may be done by preaching. Matthew tells us that Jesus said, "And this gospel of the Kingdom will be preached throughout the whole world, as a testimony to all nations; and then the end will come" (Matthew 24:14). All men must be given the chance to know and to love Jesus Christ before the end of creation is reached. The missionary activity of the Church is the hastening of the coming of the King. (iii) It may be done by penitence and obedience. Of all things this would be nearest to Peter's mind and heart. The Rabbis had two sayings: "It is the sins of the people which prevent the coming of the Messiah. If the Jews would genuinely repent for one day, the Messiah would come." The other form of the saying means the same: "If Israel would perfectly keep the law for one day, the Messiah would come." In true penitence and in real obedience a man opens his own heart to the coming of the King and brings nearer that coming throughout the world. We do well to remember that our coldness of heart and our disobedience delay the coming of the King. PERVERTERS OF SCRIPTURE

Peter here cites Paul as teaching the same things as he himself teaches. It may be that he is citing Paul as agreeing that a pious and a holy life is necessary, in view of the approaching Second Coming of the Lord. More likely, he is citing Paul as agreeing that the fact that God withholds his hand is to be regarded not as indifference on God's part but as an opportunity to repent and to accept Jesus Christ. Paul speaks of those who despise the riches of God, s goodness and forbearance and patience, forgetting that his kindness is designed to lead a man to repentance (Romans 2:4). More than once Paul stresses the forbearance and the patience of God (Romans 3:25; 9:22). Both Peter and Paul were agreed that the fact that God withholds his hand is never to be used as an excuse for sinning but always as a means of repentance and an opportunity of amendment. With its reference to Paul and its tinge of criticism of him, this is one of the most intriguing passages in the New Testament. It was this passage which made John Calvin certain that Peter did not himself write Second Peter because, he says, Peter would never have spoken about Paul like this. What do we learn from it? (i) We learn that Paul's letters by this time were known and used throughout the Church. They are spoken of in such a way as to make it clear that they have been collected and published, and that they are generally available and widely read. We are fairly certain that it was about the year A.D. 90 that Paul's letters were collected and published in Ephesus. This means that Second Peter cannot have been written before that and, therefore, cannot be the work of Peter, who was martyred in the middle sixties of the century. (ii) It tells us that Paul's letters have come to be regarded as Scripture. The misguided men twist them as they do the other Scriptures. This again goes to prove that Second Peter must come from a time well on in the history of the early Church, for it would take many generations for the letters of Paul to rank alongside the Scriptures of the Old Testament. (iii) It is a little difficult to determine just what the attitude to Paul is in this passage. He is writing "in the wisdom which has been given to him." Bigg says neatly that this phrase can be equally a commendation or a caution! The truth is that Paul suffered the fate of all outstanding men. He had his critics. He suffered the fate of all who fearlessly face and fearlessly state the truth. Some regarded him as great but dangerous. (iv) There are things in Paul's letters which are hard to understand and which ignorant people twist to their own ruin. The word used for hard to understand is dusnoetos, which is used of the utterance of an oracle. The utterances of Greek oracles were always ambiguous. There is the classic example of the king about to go to war who consulted the oracle at Delphi and was given the answer: "if you go to war, you will destroy a great nation." He took this as a prophecy that he would destroy his enemies; but it happened that he was so utterly defeated that by going to war he destroyed his own country. This was typical of the dangerous ambiguity of the ancient oracles. It is that very word which Peter uses of the writings of Paul. They have things in them which are as difficult to interpret as the ambiguous utterance of an oracle. Not only, Peter says, are there things in Paul's writings that are hard to understand; there are things which a man may twist to his own destruction. Three things come immediately to mind. Paul's doctrine of grace was twisted into an excuse and even a reason for sin (Romans 6). Paul's doctrine of Christian freedom was twisted into an excuse for unchristian license (Galatians 5:13). Paul's doctrine of faith was twisted into an argument that Christian action was unimportant, as we see in James (James 2:14-26). G. K. Chesterton once said that orthodoxy was like walking along a narrow ridge; one step to either side was a step to disaster. Jesus is God and man; God is love and holiness; Christianity is grace and morality; the Christian lives in this world and lives in the world of eternity. Overstress either side of these great two-sided truths, and at once destructive heresy emerges. One of the most tragic things in life is when a man twists Christian truth and Holy Scripture into an excuse and even a reason for doing what he wants to do instead of taking them as guides for doing what God wants him to do. A FIRM FOUNDATION AND A CONTINUAL GROWTH