compiled by Lumbar P. Doldrums, Archivist

(A Parody)

![]()

Graduation

day at San Diego State College in 1954 found me wondering if there

was any value to a college degree in physics and math. Pondering

the meaning of life I skipped the commencement ceremonies and

fired up my Tesla coil in the Physics Lab. The school had a nifty,

jim-dandy arker sparker of a coil built about 1922. But my EE

prof David Kalbfell suggested I modify it to be all-electronic.

He took me to the basement and showed me bushel baskets of Eimac

304TL power tetrodes left over from the war. Next he conned the

power company for a 15 kw 12,000 "pole pig" transformer

and the Navy for mica capacitors. During my senior year we stacked

eight 304TLs in parallel and using a Colpitts oscillator circuit

and raw AC on the plates we generated fat streams of glowing plasma

several feet long. The local IEEE chapter politely sat through

my demonstration and lecture on LaPlace transforms, network analysis,

and how to get maximum suds out of any Tesla coil old or new.

Graduation

day at San Diego State College in 1954 found me wondering if there

was any value to a college degree in physics and math. Pondering

the meaning of life I skipped the commencement ceremonies and

fired up my Tesla coil in the Physics Lab. The school had a nifty,

jim-dandy arker sparker of a coil built about 1922. But my EE

prof David Kalbfell suggested I modify it to be all-electronic.

He took me to the basement and showed me bushel baskets of Eimac

304TL power tetrodes left over from the war. Next he conned the

power company for a 15 kw 12,000 "pole pig" transformer

and the Navy for mica capacitors. During my senior year we stacked

eight 304TLs in parallel and using a Colpitts oscillator circuit

and raw AC on the plates we generated fat streams of glowing plasma

several feet long. The local IEEE chapter politely sat through

my demonstration and lecture on LaPlace transforms, network analysis,

and how to get maximum suds out of any Tesla coil old or new.

Terrified of getting a job or even of living in the real world I decided to go to Stanford. Dave Kalbfell and Prof. Lester L. Skolil Jr. wrote glowing letters of recommendation to Fred Terman, Bill Edson, Dave Petit, Hugh Skilling, Leonard Schiff and who knows who else. My best friend Leland S. Reel chose Physics at Berkeley which began our long rivalry to see which one of us could flunk out of graduate school first. HiFi had recently been invented, and yes, TV too, so my U-Haul to Stanford that fall contained my monstrous 18 inch speaker cabinet (16 cycle organ notes were a must), my 50 pound precision weighted turntable, a ton of books a million LP records and boxes of old radio parts. Like the rest of the grad students we were invited into the luxury dorms of Stanford Village (312B). This never-used WW2 hospital was frame buildings, paper thin walls (ask someone about the legends of the marriage students dorms). All the buildings were joined to the cafeteria by miles of hallways and roofs that leaked whether it was raining or not.

Stanford was not easy. I had breezed

through SDSC but my 150 physics grad school companions were all

geniuses and suddenly I was at the bottom of the heap. The school

bulletin said a PhD in four years was a breeze, but then I met

an ancient shriveled little man who lived in the old physics building

attic. Mr. Chan told me he had been there since x-rays were discovered

by Prof. Paul Kirkpatrick at the beginning of century. He allowed

as how 7-10 years was typical for a PhD and that many physics

students would probably spend their lives in the basement working

on Prof. Meyerhof's cyclotron. Many, he said would never again

see the light of day. George Johnson, an older "professional"

grad student, passed on his job to me--he was the chief lab instructor

for the freshman labs and our friendship started then. He in fact

DID get a PhD, never grew a day older, and thrives to this day

in a brilliant career at SRI. Many are the terrible things that

happened to me back then. I remember deciding to send all the

mercury from the manometers out for cleaning. So I dumped gallons

of liquid mercury into old coffee cans and left it all on Eric's

desk. (Eric was the Physics Storekeeper and he dated back to the

days Mrs. Stanford rode her bike around the Quad). Well, mercury

amalgamates nicely with other metals so all the mercury was soon

on the oiled planked wooden floor, in the desk, and scattered

in dusty clumps everywhere! I was terrified, not so much of the

wrath of the head of the department Prof. Leonard Schiff, (he

was a shy man and always slipped in and out of his office when

no one was in the halls). What I feared was getting on the wrong

side of Anna Laura Berg, who, everyone said, actually ran the

department and ruled with a rod of iron. The ordeal of my first

year was finally over so I spent the summer earning $1.25 an hour

building high voltage power supplies for the original on-campus

linear accelerator. Second year was not much better, I cowered

in fear of exams and the intimidation of the older students any

one of whom could surely win the Nobel Prize at any time. Oh,

the classes were fabulous: Robert Hofstader, Wolfgang Panofsky,

Willard Lamb, Herr Meyerhof...great men and great teachers in

a golden era for physicists.

Stanford was not easy. I had breezed

through SDSC but my 150 physics grad school companions were all

geniuses and suddenly I was at the bottom of the heap. The school

bulletin said a PhD in four years was a breeze, but then I met

an ancient shriveled little man who lived in the old physics building

attic. Mr. Chan told me he had been there since x-rays were discovered

by Prof. Paul Kirkpatrick at the beginning of century. He allowed

as how 7-10 years was typical for a PhD and that many physics

students would probably spend their lives in the basement working

on Prof. Meyerhof's cyclotron. Many, he said would never again

see the light of day. George Johnson, an older "professional"

grad student, passed on his job to me--he was the chief lab instructor

for the freshman labs and our friendship started then. He in fact

DID get a PhD, never grew a day older, and thrives to this day

in a brilliant career at SRI. Many are the terrible things that

happened to me back then. I remember deciding to send all the

mercury from the manometers out for cleaning. So I dumped gallons

of liquid mercury into old coffee cans and left it all on Eric's

desk. (Eric was the Physics Storekeeper and he dated back to the

days Mrs. Stanford rode her bike around the Quad). Well, mercury

amalgamates nicely with other metals so all the mercury was soon

on the oiled planked wooden floor, in the desk, and scattered

in dusty clumps everywhere! I was terrified, not so much of the

wrath of the head of the department Prof. Leonard Schiff, (he

was a shy man and always slipped in and out of his office when

no one was in the halls). What I feared was getting on the wrong

side of Anna Laura Berg, who, everyone said, actually ran the

department and ruled with a rod of iron. The ordeal of my first

year was finally over so I spent the summer earning $1.25 an hour

building high voltage power supplies for the original on-campus

linear accelerator. Second year was not much better, I cowered

in fear of exams and the intimidation of the older students any

one of whom could surely win the Nobel Prize at any time. Oh,

the classes were fabulous: Robert Hofstader, Wolfgang Panofsky,

Willard Lamb, Herr Meyerhof...great men and great teachers in

a golden era for physicists.

Money was tight, I was burned out so was eager for my second

summer. Housing had improved during Year Two--I was now upstairs

in a huge room of the Stanford Village Hospital (Mental Ward?).

Directly underneath me was a very neurotic grad student in chemistry

who studied all night every night. Not only did I have to walk

softly at all times, but never ever (hardly ever) could I play

my favorite organ music at full volume on my super linear push-pull

Macintosh power amplifier using British KT88s with 30 db of feedback.

At the very opposite end of the building was a red-haired EE grad

student named Myles Renver Berg. All the rooms had many extra

closets and cabinets and we arranged these as we liked. Myles

had his cabinets around his room with clothes lines stretched

between them so his laundry could dry while he slept. His hi-fi

was buried in the stacks on each side of his bed, at ear- level. In my

room I fixed all the cabinets in a U-shaped labyrinth so that

opening the door of my room one had to turn right and then left

and then left again to enter my room. Well, one night I was out

drinking beer late at Rossotti's with some of my grad student

friends and it was after 2 AM when I staggered back to my room

at Stanford Village. Opening my door I found not a labrinith but

a solid wall. The lights also did not work, and the wall reached

to the ceiling. Myles had cleverly played a joke on me knowing

that I would be forced to knock over cabinets and send them crashing

down to the floor. Sure enough after the thundering crash of my

forced entrance, the now-psychotic chem student from the room

below was at my door with the RA in tow, and murder in his eyes.

He never spoke to me again, and in fact I think he disappeared

not long thereafter. Surely I pushed him over the edge?

level. In my

room I fixed all the cabinets in a U-shaped labyrinth so that

opening the door of my room one had to turn right and then left

and then left again to enter my room. Well, one night I was out

drinking beer late at Rossotti's with some of my grad student

friends and it was after 2 AM when I staggered back to my room

at Stanford Village. Opening my door I found not a labrinith but

a solid wall. The lights also did not work, and the wall reached

to the ceiling. Myles had cleverly played a joke on me knowing

that I would be forced to knock over cabinets and send them crashing

down to the floor. Sure enough after the thundering crash of my

forced entrance, the now-psychotic chem student from the room

below was at my door with the RA in tow, and murder in his eyes.

He never spoke to me again, and in fact I think he disappeared

not long thereafter. Surely I pushed him over the edge?

Well Myles was to blame and my revenge was sweet. The next day while Myles was on campus I ran wires down the outside of the building from my amplifier to his loudspeakers and concealed the evidence. Setting my alarm for 3 AM the next night I quietly connected the wires to Myles' speakers to my amp in my room and turning up the volume to maximum fired up the Finale from the Organ symphony of Saint Saens. The whole building was flooded in sound, and Myles leapt out of bed pulling wet clothes lines down around himself as he ran into the hall. Quickly I retrieved my wires from the window and left Myles to answer for himself. I think he suspects me to this day, but our friendship was always solid thereafter. At least i think we are even!

In fact when

I told Myles I needed a summer job he said he would speak to a

friend of his in the EE Dept, a certain Dr. Peterson. June came

around and sure enough Lu Clarke at SRI had a summer job for me

at $2.25 an hour. My assignment was to install a 50 kilowatt FM

transmitter in a 40 foot van, help build a 61 foot dish, get radar

echoes from the moon and take the ensemble up to College, Alaska,

near Fairbanks. My first purchase order was for bright red rubber

floor tile for the van and I still remember this was when my reputation

as the "Last of the Big Spenders" got off to a good

start. My boss was a tall, lean, lanky fellow, Ray L. Leadabrand

who I discovered was already very very famous. It turns out Ray

had almost finished his PhD at Stanford (except for the French

exam Prof. Mike Villard later told me). Using a war surplus radar

and a ham beam antenna, Mr. Rubberband had made the astounding

discovery that field aligned ionization over Seattle could be

seen on radar from Stanford during periods of high solar activity.

Ever modest, Mr. Rubberband to this day has refused interview

requests from 60 Minutes and The Discovery Channel regarding this

dramatic, pioneering work. Anyway Mr. Rubberband lived with his

charming wife Mildew in a spiffy new Eichler home on Middlefield

and he owned a very fine green corduroy jacket and was already

in the Flying Club and the United Airlines 100,000 mile Club.

He was my instant mentor and hero and I hoped I could be like

him when I grew up (if I ever did). Ray's office mate was a short

but alert scientist, a certain W. Ray Vincent. "Well, now

wait just a minute, golly, I think, well Van Allen has activated

his radiation belt and I am not sure, well maybe, let's see, may

be we can get some meteor echoes, sort of thing.." (rocking

from side to side). Dr. Alec Montflower Patterson came through

the lab once a day and we all reverently waited to greet him as

he was light-years ahead of everyone else with his Giant Electric

Snake project and exotic plans to point the RF energy from SLAC's

thousand klystrons at the planet Venus. Dr. Pete also rocked back

and forth nervously when he talked, "Well, the calculations

show that we could trigger an earthquake on the San Andreas fault

but I'll ask Livermore to check the data." Then he rushed

off to meetings with various brilliant scientists from near and

far.

In fact when

I told Myles I needed a summer job he said he would speak to a

friend of his in the EE Dept, a certain Dr. Peterson. June came

around and sure enough Lu Clarke at SRI had a summer job for me

at $2.25 an hour. My assignment was to install a 50 kilowatt FM

transmitter in a 40 foot van, help build a 61 foot dish, get radar

echoes from the moon and take the ensemble up to College, Alaska,

near Fairbanks. My first purchase order was for bright red rubber

floor tile for the van and I still remember this was when my reputation

as the "Last of the Big Spenders" got off to a good

start. My boss was a tall, lean, lanky fellow, Ray L. Leadabrand

who I discovered was already very very famous. It turns out Ray

had almost finished his PhD at Stanford (except for the French

exam Prof. Mike Villard later told me). Using a war surplus radar

and a ham beam antenna, Mr. Rubberband had made the astounding

discovery that field aligned ionization over Seattle could be

seen on radar from Stanford during periods of high solar activity.

Ever modest, Mr. Rubberband to this day has refused interview

requests from 60 Minutes and The Discovery Channel regarding this

dramatic, pioneering work. Anyway Mr. Rubberband lived with his

charming wife Mildew in a spiffy new Eichler home on Middlefield

and he owned a very fine green corduroy jacket and was already

in the Flying Club and the United Airlines 100,000 mile Club.

He was my instant mentor and hero and I hoped I could be like

him when I grew up (if I ever did). Ray's office mate was a short

but alert scientist, a certain W. Ray Vincent. "Well, now

wait just a minute, golly, I think, well Van Allen has activated

his radiation belt and I am not sure, well maybe, let's see, may

be we can get some meteor echoes, sort of thing.." (rocking

from side to side). Dr. Alec Montflower Patterson came through

the lab once a day and we all reverently waited to greet him as

he was light-years ahead of everyone else with his Giant Electric

Snake project and exotic plans to point the RF energy from SLAC's

thousand klystrons at the planet Venus. Dr. Pete also rocked back

and forth nervously when he talked, "Well, the calculations

show that we could trigger an earthquake on the San Andreas fault

but I'll ask Livermore to check the data." Then he rushed

off to meetings with various brilliant scientists from near and

far.

Our

lab was in a part of the old Stanford Village where the roofs

leaked all the time. As I understand it they still have never

been fixed, 50 years later. The buildings were laid out like a

Mississippi river boat sunk in the mud. At the front end, up near

Ravenswood avenue and the old Sharon Estate Guest House, was the

Wheel House where Tom Morrin steered the ship of state and led

the Engineering Group into the roaring '50s. It was always a privilege

to visit the Wheel House. The old steering wheel linkage to the

rudder was broken, but I think the whistle and bell were still

working. The high muckety mucks usually wore their naval uniforms

from the Spanish-American War which added an unmistakable touch

of class.

Our

lab was in a part of the old Stanford Village where the roofs

leaked all the time. As I understand it they still have never

been fixed, 50 years later. The buildings were laid out like a

Mississippi river boat sunk in the mud. At the front end, up near

Ravenswood avenue and the old Sharon Estate Guest House, was the

Wheel House where Tom Morrin steered the ship of state and led

the Engineering Group into the roaring '50s. It was always a privilege

to visit the Wheel House. The old steering wheel linkage to the

rudder was broken, but I think the whistle and bell were still

working. The high muckety mucks usually wore their naval uniforms

from the Spanish-American War which added an unmistakable touch

of class.

We had coffee hours in the halls twice a day and I always knew when it was time to go for coffee as the booming bass voice of our electromagnetic theoretician, Dr. Pharton Klammer, would always be heard above the din at the coffee cart, "Well, that formula could not possibly be correct because you forgot to take the divergence of B into account and I see you did not integrate over all of Q space. My new paper on this is definitive. I suggest you wait for it to appear in JGR. Har-umph." Dr. Tseste Morita generally showed up for coffee in a white shirt with sleves rolled up above the elbow. His X, Y, and Z band antenna models are still being exploited around the world.

Lunch at Fabbros! Always a treat!

George Parks and David A. Johnson came on board soon, and their first job, as I recall, was tying screen on our first radar dish on campus. This first giant steel framework disk (GSFD)--61 feet in diameter--was spindly but a beautiful masterpiece designed on the back of a match cover by an incredibly intuitive mechanical engineer named Steel Nafford. Mr. Stafford insisted the disk was plenty strong (it could be winched up and down for changes to the feed)--yet the first winter always found Mr. Rubberband calling one of us to get out of bed and make sure the guy wires were in place when the winds roared in. That got old in a hurry. It was worse when Sputnik happened because Mr. Vincent built an Eichler home at the field site and we had to record every satellite pass night or day with Dr. Patterson taking notes and talking to the President (I think) on the White Courtesy Phone.

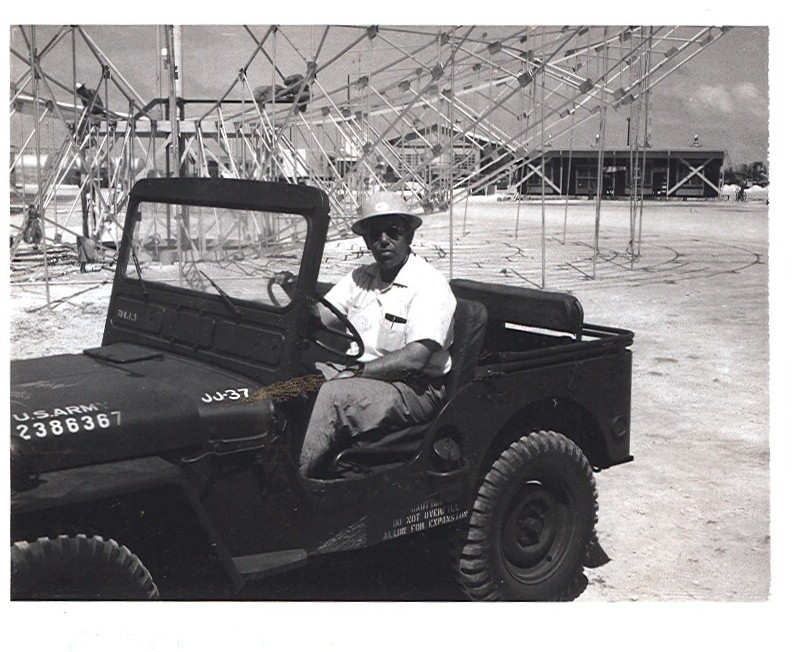

"Mirror, Mirror on the Wall..."

Prize Winning Photo of youthful Project leader at Stanford

Field Site, 1955.

We all drove to and from the Stanford Village, the headquarters of SRI, and the field site in an ancient 4X4 all purpose humungous vehicle and we had to negotiate locked gates which were zealously guarded by one Immanuel Peers ("Farmer Peers"). Peers had a dairy and grazed his cows on leased land from Stanford, and had done so for generations as far as I knew. "You guys be real careful and don't let the bulls in with the cows. Next time I'll get my shot gun." "I plead guilty sir, we will be more careful next time," I promised when the inevitable happened and Farmer Peers' herd took a quantum jump in size. Peers was a neat guy--on Sundays he took his friends fox hunting at the field site--everyone all dressed in English riding style. I think the dairy is still there?

Well them early days was already getting hectic. It seems Dr.

Alec Montflower Patterson had gone to the Pentagon and come home

with a portfolio of big, important projects the government wanted

done yesterday--in order to fend off impending nuclear war with

the Russians. I knew how to spend money and Mr. Rubberband knew

how to roll heads! (He was awesome). His arch opponent in Upper

Management, Ray's Simon Lagree, was our very proper ever-beloved

by-the-book ever-foot-dragging Chuck Hilly. Oh, yes, I forgot

to introduce Gordon Rosekilly, of Rosekilly Machinery, San Mateo,

who was always at my door to sell us junk. (see photo). When Frank

Firth built our first hi-powered TR switch, Mr. Rosekilly immediately

delivered a wonderful 1930 model Rootes Blower, which  upon

being demonstrated, spewed dirty oil and fumes all over our lab.

Omar Spain was SRI Facilities Manager, Walter Jaye was our effective

rising manager type, and well so far you have met the rest of

the illustrious team members in the above photo as they all met

for a High Level meeting in 1957. Yours truly is shown wearing

the ever-popular official Lab tee shirts with a portrait of our

Great Leader, Mr. Rubberband, and the helpful reminder "What

Me Worry?" which was later stolen, rumor has it, by Mad Magazine.

They made lots of bucks on our logo that's for sure.

upon

being demonstrated, spewed dirty oil and fumes all over our lab.

Omar Spain was SRI Facilities Manager, Walter Jaye was our effective

rising manager type, and well so far you have met the rest of

the illustrious team members in the above photo as they all met

for a High Level meeting in 1957. Yours truly is shown wearing

the ever-popular official Lab tee shirts with a portrait of our

Great Leader, Mr. Rubberband, and the helpful reminder "What

Me Worry?" which was later stolen, rumor has it, by Mad Magazine.

They made lots of bucks on our logo that's for sure.

The radar went together fairly smoothly. Leadabrand wanted more power so we doubled the voltage on the final RF power amp and cranked up the front-end drive to overload. ("More drive, I want more drive..." Ray always said.). The outside 440-volt circuit breaker was not too reliable and when some gigantic arc-overs threatened to burn up the transmitter, van and all, our wonder boy engineer Ronald PreTzell rigged up a giant golden watch fob (a solenoid, heavy weight and chain) to the Panic buttons so we could kill all the power if we had to. Running the transmitter way beyond Westinghouse specs was hairy at times, with corona buzzing in the back room and the coax feeds arcing over in the night sky--but the data came in and we had amazing radar echoes from the moon. Meteors, too showed up nicely on the screen.

The proposed SRI Giant Hydrogen-Filled Steel Framework Dirigible (GHFSFD) with 75 foot foot dish and spark gap radars, compared with a sleazy 747 and the ill-fated Titanic. Match cover sketch by Steel Nafford. |

When it came time to build more dishes we were ready. The second major GSFD, 150 feet in diameter, was another masterpiece conceived by Steel Nafford, and built face up on the ground. It was finally lifted onto its mounts by L.L. Bean Rigging Company using the two largest cranes in the Bay Area on a Sunday morning. This disk was light weight and cheap compared to the million dollar precision dishes the Andrew Corp was building everywhere by that time. Mr. Dewey Bunson Berner from Hiller Helicopters of East Palo Alto came along to help Neil Stafford build the light weight dish proper. It was built of aluminum struts inward and outward from a giant steel ring. Sir George Durfey, ever resourceful, adapted Navy gun turret hydraulic drives to turn the thing around on its circular railroad track and soon young Murray Barroom had a PDP11 tracking computer installed and the disk was ready. Noise levels being high at Stanford the disk found limited usefulness for receiving but continues to be useful to the present day mostly for impressing out of town visitors and potential clients. And, it is the prototype for others of its kind, one of which was sent to Scotland which allowed our very own boy scientists Schlow Johnbohm an opportunity to rent a castle and go after high latitude auroral echoes. I got to go to Adelaide and Woomera to plan for our 85 foot disk there and came back a confirmed tea drinker and a temporary Australian accent. And so on, and on and on...

![]()

|

Our Ever-Inspiring Glorious

Leader

|

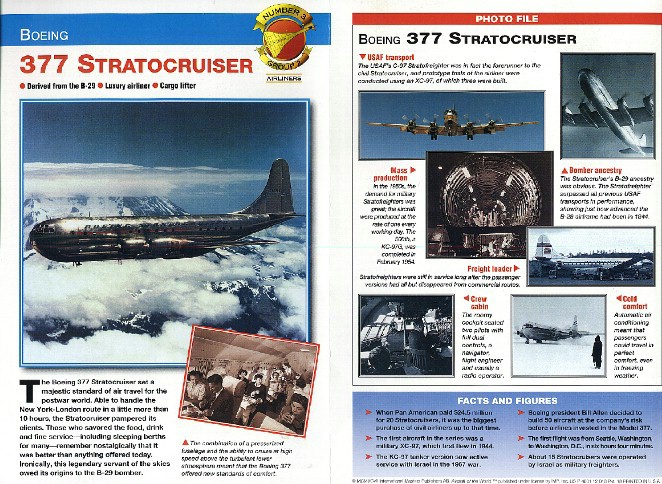

My first ride in an aeroplane was in 1956. Mr. Leadabrand said I could go to Fairbanks with him. Our Western Airlines DC6b zoomed us up to Seattle where we boarded--at midnight--the Pandemonium World Scareways flight to Alaska. PanAm was really classy in those days with stewards and stewardii upstairs and downstairs in their giant luxury liners--tri-motored Boeing Stratocruisers (converted WW2 bombers). At first I did not understand the tri-motor appellation until I found out that these four-motored planes with their 10 foot 4-bladed props were grossly underpowered, almost always always lost an engine on take off--or half way across the Pacific from a runaway prop--and they were said not to be able to fly on three. Fifty-five gallons of oil went with each engine and all of this ended up splattered on fuselage and windows after a typical flight, dimming one's night time view of the white hot exhaust manifolds. The Stratocrusers were certainly quiet inside and the seats were lush and padded so the fact that we were lucky to get 200 knots was acceptable. J. Loren Dye later kept a log book of the names painted on the front of these PanAm planes: The Seven Seas, The Northern Lights, The Queen of the Skies, The Monarch of the Skies, The Southern Cross, and we all kept track of which plane we were on whenever we flew--until Loren found out that whenever PAA lost a plane at sea they seemed to just shift the names around so no one was the wiser.

On my very second Stratocruiser flight we lost an engine and

landed at Bellingham. Years later flying from the Marshall islands

to Hawaii in a military version a C97 our engine-out experience

diverted us to a long miserable wait for repairs at Guam. But

the pilot led me come up front in the flight and the view out

the front was superb--great windows from floor to ceiling. The

early days of flying for SRI got better when DC7s came along.

They were very loud but much faster. One could fly all night to

DC on the red-eye special, work all day at the  Pentagon and fly home via a refueling

stop in Chicago that same day. Ray thought we young engineers

should commute back east at least once a month just to keep fit.

Finally the luxurious Lockheed Super Cancellations came along

with their very reclining seats and faster turbo-charged ride.

I shall never forget my first 707 ride--New York to Miami in the

days when PanAm had the only jet flight in the country. Shortly

after that TWA started their 2:15 PM daily trip from SFO to Dulles

and crowds lined up at the airport to watch a real, live 707 take

off after using up all the runway and water injection besides.

It was a long wait before Travel could get us reservations.

Pentagon and fly home via a refueling

stop in Chicago that same day. Ray thought we young engineers

should commute back east at least once a month just to keep fit.

Finally the luxurious Lockheed Super Cancellations came along

with their very reclining seats and faster turbo-charged ride.

I shall never forget my first 707 ride--New York to Miami in the

days when PanAm had the only jet flight in the country. Shortly

after that TWA started their 2:15 PM daily trip from SFO to Dulles

and crowds lined up at the airport to watch a real, live 707 take

off after using up all the runway and water injection besides.

It was a long wait before Travel could get us reservations.

Well this true story is not about airplanes, actually. We all had tales to tell about flying because it was not long before Mr. R. and Mr. Vincent had projects all over the world and we all got to fly all the time. Since we had been told that work was fun we never doubted our great leader's call for more drive, or his cry "Faster" uttered in the halls ways when work seemed to be slowing down. But speaking of flying. a careful observer noted that Dr. Patterson could not be both in Washington DC briefing the President and Joint Chiefs AND teaching classes and running Engineering projects at SRI all simultaneously. Aftre hiring a private eye we learned that there existed two identical Dr. Pattersons, affectionately known as "I" and "II"--and that (quantum mechanically speaking) the average position of either of the two Dr. Petes was 35,000 feet over Kansas City at any given time. A portrait of our Founder and Very Great High Glorious Leader (F&VGHGL) found its way into the lobby where is probably resides to this day?

Came time to take the Stanford 61 foot dish to Fairbanks. It all got shipped by barge and rail and truck, and arrived in the dead of winter so Mr. Leadabrand and I went up and assembled the dish upside down in the snow, and with a little help we tied on the screen, too. A couple of months later J. Loren Dye and I went up to connect the dish to the mount. Our first exciting adventure was meeting Bud Hilton of Hilton's SteamThawing Service. Seems as if 40 below in Fairbanks can be troublesome if you want to pour concrete or get frozen snow off of a radar dish, but Bud showed up with truck and huge boiler and set us free in short order midst clouds of steam and artificial ice fog. It was at the Geophysical Institute that I first met a very nice grad student in wool shirts and jeans by the name of Bob Leonard. A young lady named Carol and Bob and a bunch of us from SRI took a trip down to Nenanna to see an old gold dredge on the Tanana River that winter--all lots of fun. In winter the sun comes up in Fairbanks in late morning, it grazes the southern sky and night sets in about 4 PM. There is not a lot else to do. We did eat well at the Fairbanks Inn, always on the look out for our favorite waitress, Miss Structurally Unsound, whose hour-glass figure narrowed at the waist to the vanishing point. We made jokes about our favorite bars being open 24 hours and since it was hard to tell when it was not night we could stay out too late all too easily. "Did I see the Institute vehicle parked in front of the Diamond Horsehoe again last night" asked someone from the Geophysical Institute on several occasions.

|

Mr. Leadabrand commends our Large Scale organ builder, Dick Stenger, who has just given a wonderful performance on a real steam calliope in the High Bay of Bldg 44. About 1972 I think. |

Dedication speech by Slim Rubberband presenting authentic photo of our Glorious Founder, Alex Montflower Patterson I, II, to Commodore Lumbar Doldrums on the occasion of Doldrums sabbatical leave. |

Young Dick Stenger, one of our all time best and most ingenious technicians was also the Large Scale Organ builder for Casavant Freres of Montreal had earlier he had introduced Roy Long and me to the wonderful world of pipe organs. We three, with organist C. Thomas Rhoads often visited all the major Bay Area theaters after the last movie show and climbed the organ lofts, and in fact we gave away a year of weekends restoring the Wurlitzer theater organ at the Lost Weekend Bar at 19th and Taraval in San Francisco for musician Larry Vannucci who became a dear friend. Roy even flew us in his overloaded Cessna to LA for a full weekend of church organ touring.

Well

anyhow it was while Dick and J. Loren and I were in Fairbanks

that we discovered that the Empire Theater had a pipe organ left

over from the silent film days! Naturally we dropped out vital

government project work and got the old Hope Organ playing again.

The above libelous, untrue, fictional story by Jim Hodges borrows

an actual daguerreotype of the work underway at 2 AM in the Empire

Theater where our visionary leader Lumbar is vacuuming stale popcorn

from the main pipe chest. Stenger was at the console at the time

testing the hydraulic lift which was gummed up with old coca cola.

In all fairness, Mr. Hedges is a likable, congenial person but

he always got his facts mixed up trying to make up the funniest

stories to post outside of the Lab Manager's office and later,

upstairs, on the Lambert Dolphin Memorial Bulletin Board. Mr.

Hodges was well intentioned, we do acknowledge that fact. Anecdotally,

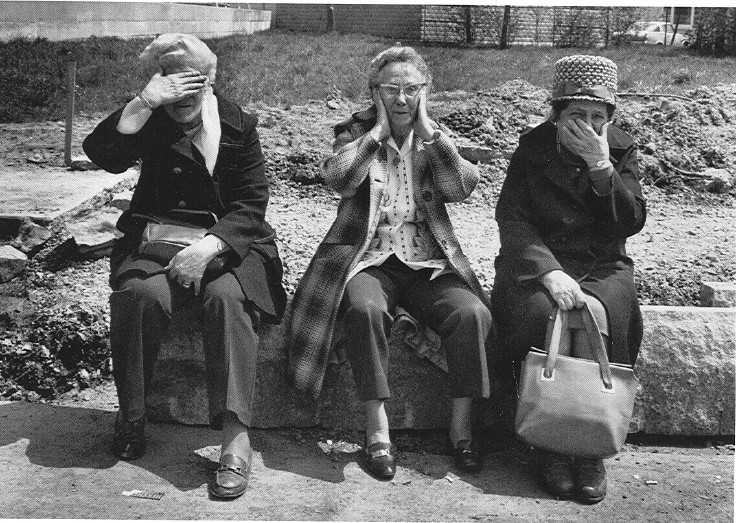

I think it worthwhile to mention my meeting with the Fairbanks

Chamber of Commerce and Ladies Aid society in Fairbanks in the

early years (see photo, right). In a press interview describing

the wonders of streaming charged particles from the sun becoming

trapped in the magnetic field lines and ending up in Alaska, Dr.

Patterson's remarks at a public meeting at Traveler's Inn had

caused some careless, unnamed reporter to write that Dr. Patterson

had come to their state with a new machine that could "turn

off the aurora." The ensuing alarm and phone calls to E.

Kinley Karter, SRI president, necessitated a series of home meetings

to calm the local populace.

Well

anyhow it was while Dick and J. Loren and I were in Fairbanks

that we discovered that the Empire Theater had a pipe organ left

over from the silent film days! Naturally we dropped out vital

government project work and got the old Hope Organ playing again.

The above libelous, untrue, fictional story by Jim Hodges borrows

an actual daguerreotype of the work underway at 2 AM in the Empire

Theater where our visionary leader Lumbar is vacuuming stale popcorn

from the main pipe chest. Stenger was at the console at the time

testing the hydraulic lift which was gummed up with old coca cola.

In all fairness, Mr. Hedges is a likable, congenial person but

he always got his facts mixed up trying to make up the funniest

stories to post outside of the Lab Manager's office and later,

upstairs, on the Lambert Dolphin Memorial Bulletin Board. Mr.

Hodges was well intentioned, we do acknowledge that fact. Anecdotally,

I think it worthwhile to mention my meeting with the Fairbanks

Chamber of Commerce and Ladies Aid society in Fairbanks in the

early years (see photo, right). In a press interview describing

the wonders of streaming charged particles from the sun becoming

trapped in the magnetic field lines and ending up in Alaska, Dr.

Patterson's remarks at a public meeting at Traveler's Inn had

caused some careless, unnamed reporter to write that Dr. Patterson

had come to their state with a new machine that could "turn

off the aurora." The ensuing alarm and phone calls to E.

Kinley Karter, SRI president, necessitated a series of home meetings

to calm the local populace.

"Put the book down Daniel, Roy needs you.

Lambert has crashed the KL10 again"

SRI New Years' Party CA 1955

Ray Irvine at the Piano

Building 320 was our second home after moving out of our tiny barracks in 404E. I think 320 might have been the old hospital morgue, but we made do. I started building spark transmitters on the roof after visiting a mad scientist in Australia named Kurt Landecker who claimed he could generate vast amount sof RF pulse power by charging capacitors in parallel and discharging them in parallel in a radiating loop or ring. Mr. Rubberband by this time had hired an exceptionally bright and highly spirited young secretary, Miss Jane Osterizer. (She later married Murray Baron but was unable to launch him into an orbit around Mars despite repeated efforts). I remember the hassles we had getting enough phones. Ray had the first speaker phone ever invented and we all used it to call friends when Ray was back East. Well another near-fatal fiasco or mine was organizing a dedication for Ray's new office. Someone (not me!) painted Ray's great oak desk flaming pink and we all recklessly filled his office with very large meteorological balloons--filled with water. As I said, this was one one several great disastrous mistakes of my life for which there is no forgiveness to be had on judgment day, and on top of that Ray was not amused. Soon after that Ma Bell announced they were doing away with phone number prefixes such as KLondike 7 or MEridian 6 and Ray decided to roll heads. Either the phone company cease and desist and leave us with our colorful history or we would take our business elsewhere, Ray told the CEO or some high muckety muck at PacBell. But our loud protests were in vain--there was only one phone company to choose from back then.

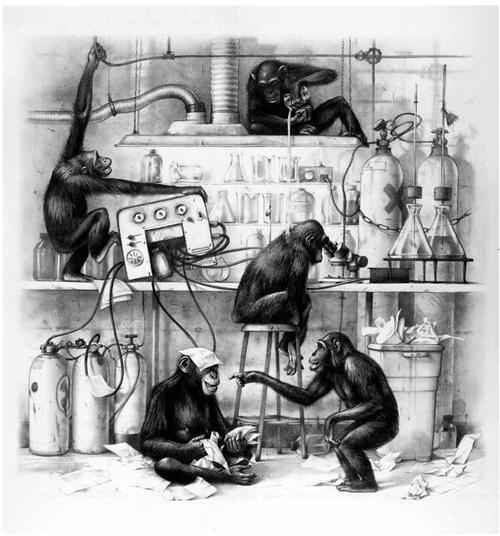

Working Environment in the 60s and 70s (typical)

We grew and grew and now the Communications Group under Vincent headed off to be their own lab and RPL marched ahead boldly. Slim Rubberband solicited all our inputs on a new Building 44. It had to have a hydraulic elevator with front and back doors and a huge High Bay capable of holding an 85 foot dish under construction and who knows how many 40-foot vans. It had sealed windows and individual thermostats with hot and cold air plenums over every office. The roof was extra strong for antenna work, but Steel Nafford had designed the high bay roof trusses so we were all a bit careful up there.

From the Menlo Park City Hall across the street the city fathers could see that we had built a respectable 2 story concrete office and lab. But secretly added was the Third Floor restauraunt featuring Joe Wagner's All-Girl orchestra with Dinner Dancing. Our ballroom could only be reached by the sticky hydraulic elevator, so access was a bit slow on Friday nights. For safety's sake Mr. Nafford built us an escape slide in the back, taken from a crashed Boeing Stratocruiser cabin door. Joseph preferred Viennese waltzes (having been raised in Austria) but RLL sent him off to dance-band school and Joe added steel drums from Antigua and other exotic instruments collected by our brilliant scientists on their world travels. Ever popular over the years, Vagner added a line of chorus girls from Stanford and belly-dancers flown in from Cairo. The latter were hand picked by our own Bob Bollen from the 23rd Floor of the SherAtone Hotel Night Club on the Nile, and most of them looked OK if the lights were kept dimmed.

|

|

Dedication date for Building 44 was a gala affair with helpful placards located throughout the building so people could find the Blue Room, the Red Room, the War Room, the restrooms, and the restauraunt. Mr. L's office was of course properly festooned with flags and banners and "What Me Worry?" posters put into place by this unnamed but well-meaning, dedicated ever-helpful lab staff member. Trouble was, Mr. Alvin Van Every from ARPA showed up for a visit on opening day and Mr. Leadabrand had to run through the building hiding signs that might be misleading to our benevolent funding agency. Not funny McGee, after all, sad to say.

It came time for more nuclear tests by our government and they

needed radar work done out in the Pacific by our lab. I flew to

Astoria, Oregon to check  out

coast guard cutters and destroyers as a possible platform and

we even inquired about an aircraft carrier (The Giant Hydrogen-filled

Dirigible-with-75 foot-steel-framework-disk-in-the-nose Project

came later). John V. N. Granger who was high up in the lab when

I came on board had his start up company going and he said his

whiz kid high school student Gordon McGinnity could build three

radars for us in 3 months. Desperate to find a practical way to

get the radars on site, Dick Stenger and I flew to Newport Beach

where yacht broker George Michaud found us the biggest and best

yacht he had--the Motor Vessel Acania--a luxury twin diesel with

teak decks built for Actress Constance Bennett in 1929. Signing

the lease Dick and I got on board and spent a very sea-sick weak

end sailing from Southern California to our berth at Treasure

Island. The ship was sturdy and sound but would roll 30 degrees

in mild swells, pitch violently when pointed into the wind and

waves, and wallow like a drunken fat lady in a following sea.

But she was fast: 10 knots! You can imagine Mr. Hilly's ire when

I sailed into port and placed a 100k of rush purchase orders the

same day. The government, Hilly said, would never allow us to

lease a ship, certainly not a yacht, and the Air Force who we

worked for by National Policy was not allowed around ships. Well,

Mr. Leadabrand rolled heads and we kept the Acania for years and

years and years! The Acania needed lots of work: air conditioning,

a 200 kw generator, a water distillation plant, fuel tanks, water

tanks--and of course five big radars all crammed into the main

salon. Stafford's 30 foot dish folded down nicely on the after

deck, the gun-mounted yagi array up front was stowable and we

even added a 75 foot cranked up tower later on for upper atmospheric

sounding with a nifty new HF step sounder. A trip to MSTS in Seattle

brought me to the office of a wonderful retired captain, Harold

Berg, who agreed to sail us to the South Pacific. Mr. Swengler

agreed to go to Hawaii for the ride and the ship left in the middle

of a great winter storm. Unlike the Titanic, the Acania was unsinkable,

but never a smooth ride, so Mr. Stenger lost 200 pounds (we think)

and was sick and forlorn when photographed at the Aloha Pier in

Honolulu after 14 days strapped into his bunk.

out

coast guard cutters and destroyers as a possible platform and

we even inquired about an aircraft carrier (The Giant Hydrogen-filled

Dirigible-with-75 foot-steel-framework-disk-in-the-nose Project

came later). John V. N. Granger who was high up in the lab when

I came on board had his start up company going and he said his

whiz kid high school student Gordon McGinnity could build three

radars for us in 3 months. Desperate to find a practical way to

get the radars on site, Dick Stenger and I flew to Newport Beach

where yacht broker George Michaud found us the biggest and best

yacht he had--the Motor Vessel Acania--a luxury twin diesel with

teak decks built for Actress Constance Bennett in 1929. Signing

the lease Dick and I got on board and spent a very sea-sick weak

end sailing from Southern California to our berth at Treasure

Island. The ship was sturdy and sound but would roll 30 degrees

in mild swells, pitch violently when pointed into the wind and

waves, and wallow like a drunken fat lady in a following sea.

But she was fast: 10 knots! You can imagine Mr. Hilly's ire when

I sailed into port and placed a 100k of rush purchase orders the

same day. The government, Hilly said, would never allow us to

lease a ship, certainly not a yacht, and the Air Force who we

worked for by National Policy was not allowed around ships. Well,

Mr. Leadabrand rolled heads and we kept the Acania for years and

years and years! The Acania needed lots of work: air conditioning,

a 200 kw generator, a water distillation plant, fuel tanks, water

tanks--and of course five big radars all crammed into the main

salon. Stafford's 30 foot dish folded down nicely on the after

deck, the gun-mounted yagi array up front was stowable and we

even added a 75 foot cranked up tower later on for upper atmospheric

sounding with a nifty new HF step sounder. A trip to MSTS in Seattle

brought me to the office of a wonderful retired captain, Harold

Berg, who agreed to sail us to the South Pacific. Mr. Swengler

agreed to go to Hawaii for the ride and the ship left in the middle

of a great winter storm. Unlike the Titanic, the Acania was unsinkable,

but never a smooth ride, so Mr. Stenger lost 200 pounds (we think)

and was sick and forlorn when photographed at the Aloha Pier in

Honolulu after 14 days strapped into his bunk.

Actually Mr.

Stenger did not exactly like the food on board the Acania. Our

cook, Hans, pictured here with Commodore Doldrums during a 30

degree roll, stored only cabbage, sauerkraut, and nachwurst in

the deck produce lockers and forepeak freezers. Enroute to the

South Pacific Stenger in a fit of unbridled frenzy threw overboard

hundreds of pounds of frozen nachwurst--poisoning fish and sharks

for miles around, and forcing our 10 man crew to eat canned chili

and peanuts from the ship's bar for the rest of the voyage. In

port, Hans stocked up just as he always had, nachwurst and cabbage.

Actually Mr.

Stenger did not exactly like the food on board the Acania. Our

cook, Hans, pictured here with Commodore Doldrums during a 30

degree roll, stored only cabbage, sauerkraut, and nachwurst in

the deck produce lockers and forepeak freezers. Enroute to the

South Pacific Stenger in a fit of unbridled frenzy threw overboard

hundreds of pounds of frozen nachwurst--poisoning fish and sharks

for miles around, and forcing our 10 man crew to eat canned chili

and peanuts from the ship's bar for the rest of the voyage. In

port, Hans stocked up just as he always had, nachwurst and cabbage.

The radars weren't all finished yet so a bunch of us joined the ship in Honolulu and rebuilt the radars radically as we sailed pitching and tossing and tolling and heaving to Entiwetok Lagoon where our tiny craft the Acania looked like a row boat alongside all the carriers and battleships of our sister projects. But we cleared port and went down to lovely Wotho atoll where we anchored awaiting for our particular bomb tests to come up on the schedule. Trips ashore helped us to appreciate native life on exotic tropical lagoons with native dancing girls. These experiences finally culminated in Alan Selby's vanishing into the culture on Raratonga in 1962 where he began to be the object of many legends and true stories that are but another part of the glorious heritage of the lab. The radars never did work right in the Marshall Islands--the time frame was simply do short to work such miracles, but the tests we were there for were delayed in time and also moved to Johnston Island so we had a reprieve in Honolulu.

Our project paper work had been hastily sent down through channels from the Highest Levels of the Pentagon and finally trickled down to Commander Field Command AF SWAP at Albuquerque. I was summoned to fly down (via TWA Constellation) to ABQ where I bonded immediately with Lt. Col. Ed. Halligan who was assigned to lead me step by step through stacks of red tape and paper work our project required in order to get us on site and relocated. I was horrified with the thought of all the paper work that had to be done right and in military jargon, too, and 12 copies. I commuted that spring (Pan Am again) some 8 times to Hawaii fixing radars and had no time to fill out forms. The Air Force did not own any ships and had no idea of fore and aft or bilge pumps and martinis on the fantail before dinner. They were in for a long, but proud learning curve and ended up with a gen-U-ine navy after all. I really liked Col. Halligan. He talked acronyms and numbers non-stop so I had to generate my own dictionary. (Mr. L. showed me the first HP hand held calculator about that time, only $395, good for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing, but not yet anywhere near a Franklin language dictionary). Well, the forms got filled out for the ship's motley crew--(it turns the first crew of 10 were from the very dregs of the docks of San Francisco). Our agents, Pillsbury and Martignoni, long term SF ship chandlers, had done well for us except in the matter of our crew. But Captain Robert Fall who joined us after Entiwetok was very capable and gradually we learned how to sail the old ship as a yacht not a Liberian freighter. Roy Long ran the Acania well into the next decade getting better and better at food and amenities and congenial crew members as well as superbly functioning equipment including scuba gear and wind surfing gear of course.

![]()

Lots of money spent in haste at Honolulu shipyards and the

ship sailed a few months later with a minimal crew the 700 miles

to Johnston island while the  rest

of us flew MATS in giant drafty swaying C124 flying boxcars. We

had a bit of hassle at Hickam AFB as the passenger manifest showed

a missing man, a certain Michael Victor Acania. When we told the

desk sergeant we had sent Michael on ahead, a security crisis

of great magnitude ensued and (as I recall) we had to roust Col.

Ed Halligan out of bed in ABQ to get the Air Force Navy back on

track. We all liked JI. Our on board ship food was better, and

we had fantail luxury whereas the other projects and MPs ashore

languished in stuffy stifling hot tents and barracks with food

catering provided by Holmes and Never (pardon me, that's "Narver").

The lagoon at JI was not crystal clear as it had been at Wotho

but we enjoyed some scuba diving amongst the sea snakes, and snail

boating in our dinghies. Night and day Arch McKinley and the rest

of us fussed with radars, clip leading 30 kilovolt leads haphazardly

everywhere while squeezed in between the wet salon windows and

the huge transmitter cabinets. Mr. Leadabrand showed up on a VIP

flight in time for the big tests and we hastened to tape all the

knobs and dials in place with "No Tweaking" signs everywhere.

rest

of us flew MATS in giant drafty swaying C124 flying boxcars. We

had a bit of hassle at Hickam AFB as the passenger manifest showed

a missing man, a certain Michael Victor Acania. When we told the

desk sergeant we had sent Michael on ahead, a security crisis

of great magnitude ensued and (as I recall) we had to roust Col.

Ed Halligan out of bed in ABQ to get the Air Force Navy back on

track. We all liked JI. Our on board ship food was better, and

we had fantail luxury whereas the other projects and MPs ashore

languished in stuffy stifling hot tents and barracks with food

catering provided by Holmes and Never (pardon me, that's "Narver").

The lagoon at JI was not crystal clear as it had been at Wotho

but we enjoyed some scuba diving amongst the sea snakes, and snail

boating in our dinghies. Night and day Arch McKinley and the rest

of us fussed with radars, clip leading 30 kilovolt leads haphazardly

everywhere while squeezed in between the wet salon windows and

the huge transmitter cabinets. Mr. Leadabrand showed up on a VIP

flight in time for the big tests and we hastened to tape all the

knobs and dials in place with "No Tweaking" signs everywhere.

Flashback note: Mr. L. liked to turn knobs a lot and had previously aroused the ire of Sir Ron PreTzel in Alaska who didn't like anyone turning his dials, "Now see here, just tell me what you want and I will make it work the way you want, but no tweaking the high voltage. I am sick, sick to giant death of you guys coming in here and ruining my radars and arcing over my klystron and tracking snow and ice on my nice waxed floor. Go back to the Traveller's Inn and I'll call you when there is aurora for you to watch and you can take Polaroid pictures." The expression "Sick to Giant Death" became a watchword ever after, etched in the minds of the next generation of would be knob tweakers. Later, Hank Olsen built stuff without real knobs on front panels (they were in back) and he put lots of fake "Leadabrand knobs" on the front panel that could could be tweaked harmlessly. Sad to say, we young bucks did cause Mr. L. lots of pain and grief because he was the last of the great knob tweakers. Firing up an old APS World War I radar one day I saw him masterfully pull in clutter echoes from B29s over Berlin long after the war had ended. Ray really was good and he knew auroral echoes when he saw them. Years later when Rolf Dycehere thought he had discovered tropical aurora at Antigua during martini hour on the fantail, our Glorious Leader immediately confirmed the result and procured another million dollars from Mr. Van Every for ongoing work.

Well the nuclear tests at JI were

unforgettable. I got to stay on the ship during the events as

did Ray and our chief engineer and the Captain and a couple of

others. We fired up the 200 kw generator, and the fire pumps and

had the lifeboats checked out and ready. Everyone else was evacuated

a safe distance away and dropped on the board the Carrier USS

Boxer. Sounding rockets launched vertically upwards from the Island

came crashing around us during the test. We had carefully covered

our nice teak rails with aluminum foil in case of flash burns

and our tiny crew on board the Acania that night experienced an

unforgettable, lifechanging event which is forever etched in our

memories. Juggling finniky radars all night, and changing Dick

King's Ampex 12-channel tape reels frantically we grabbed all

the data we could, little knowing that that very data would be

studied endlessly for many years to come. The ship did not sink

and next morning I gave the Project 7.1 preliminary test report

at a meeting of Generals and Admirals and staff scientists and

rocket experts and the bomb designers. I was only 26 at the time

and certainly did not yet know which way was up. But Mr. Leadabrand

was great about delegating responsibility and he knew we would

all grow faster if we were working way over our depth with far

too much too do and no time to do it in. He allowed us to make

our own mistakes, and mine were many, frequent--and often near

disasters. Oh, yes, I need to say one word about April Weather.

We were allowed ham radio in those days and our ancient veteran

Ray Irvine was able to work the world from the South Pacific and

also send a daily "Weather Report" in the clear back

to the lab in Menlo Park. Ahead of time we had newsy codes planned

that would tell the folks at home about health and morale and

we could pass on sea sickness reports. We could also place orders

for supplies. I remember ordering one million feet of plumber's

tape one day when I was frustrated with equipment falling out

of relay racks. Good old plumber's tape was perfect, but when

the million feet arrived we had quite a time storing it ever after.

Well the nuclear tests at JI were

unforgettable. I got to stay on the ship during the events as

did Ray and our chief engineer and the Captain and a couple of

others. We fired up the 200 kw generator, and the fire pumps and

had the lifeboats checked out and ready. Everyone else was evacuated

a safe distance away and dropped on the board the Carrier USS

Boxer. Sounding rockets launched vertically upwards from the Island

came crashing around us during the test. We had carefully covered

our nice teak rails with aluminum foil in case of flash burns

and our tiny crew on board the Acania that night experienced an

unforgettable, lifechanging event which is forever etched in our

memories. Juggling finniky radars all night, and changing Dick

King's Ampex 12-channel tape reels frantically we grabbed all

the data we could, little knowing that that very data would be

studied endlessly for many years to come. The ship did not sink

and next morning I gave the Project 7.1 preliminary test report

at a meeting of Generals and Admirals and staff scientists and

rocket experts and the bomb designers. I was only 26 at the time

and certainly did not yet know which way was up. But Mr. Leadabrand

was great about delegating responsibility and he knew we would

all grow faster if we were working way over our depth with far

too much too do and no time to do it in. He allowed us to make

our own mistakes, and mine were many, frequent--and often near

disasters. Oh, yes, I need to say one word about April Weather.

We were allowed ham radio in those days and our ancient veteran

Ray Irvine was able to work the world from the South Pacific and

also send a daily "Weather Report" in the clear back

to the lab in Menlo Park. Ahead of time we had newsy codes planned

that would tell the folks at home about health and morale and

we could pass on sea sickness reports. We could also place orders

for supplies. I remember ordering one million feet of plumber's

tape one day when I was frustrated with equipment falling out

of relay racks. Good old plumber's tape was perfect, but when

the million feet arrived we had quite a time storing it ever after.

I do want to mention our dear colleague Dr. Rolf Dycehere, a really bright young scientist just coming into puberty whom Mr. Leadabrand had adopted on one of his trips back East. I think Dycehere had been to Cornell or Lincoln Labs and it was said he knew the great Gordon Pettingill and had actually seen the Lincoln labs radar dome in person. The photo at right taken using one of our scope cameras shows Murray Baron disguised to look like Dr. Dycehere reading an inflammatory cheap pulp sci-fi novel. Rolf was actually outside at the pier waiting for the boat out to his riometer shack on a remote island. In the background Mr. PreTzel mans the radar controls and in the rear J. Loren Dye is obviously soldering something under the total masterful direction of the Radar Master. The van may look cozy (it had cots in back) and it was very hot with 100% humidity outside, but Ron kept the air conditioning blasts at near zero which he found comfortable even with shorts on, unlike the rest of us. Dr. Dycehere always wore shorts even at high level meetings in the Pentagon. "Oh dear me, my goodness, Ray, I seem to have lost my riometer charts. Can you hand me that match cover and a pen and I'll scribble the curves out here so General Folderol here can see the absorption in the D layer caused by overflying goonie birds." "Well, I don't know I never thought about that I suppose we would jury rig a scarecrow to keep the damn (excuse me, Ray that was not polite of me) birds off my antennas." Rolf did great work later on, raking leaves out from under the crater dish at Arecibo and sweeping the catwalk out to the feed point. We are reminded that a good scientist is not ashamed to sweep out his van and change the ink wells on the chart recorders.

The next round of tests at JI in '62 were more sane as far as lead time, and more sensible equipment-wise as Ron PreTzel had time to build good radars and Holmes and Never built us a new big dish on JI after new specs from the ever creative Steel Nafford (his collection of match cover sketches is, we think, in the Foothill Electronics history museum). The next nuclear test series under the direction of General Birdseed (sp?) was frustrating and long drawn out. I snitched a piece of blown up Redstone missile fuel pump from the runway after one failed test, and Mr. R. still uses it to this day as a radioactive paperwork as I recall. Dr. Water Closet assumed a major role behind the scenes about that time. He kept four secretaries busy at all times and was the perfect model of a brilliant, eccentric, dazzlingly gifted --but not always practical--great scientist we could all emulate. When I was around him I always wished I could remember my freshman physics a bit better. I always had a hard time about these guys with brains. It never bothered Ray that he had flunked French and was almost, but not quite a real doctor, but in a way I always wished I had stayed on at Stanford for another decade and had Mr. Chan tutor me until I passed all my comp exams. Still, I would have missed a lot of swashbucking adventure had I done so, and a lot of PhDs I met were really quite dull and boring people.

Sir Neil Stafford at Johnston Island about 1962 or so.

|

"Murray, sir, I deny putting 10 kilovolts into the front end of this $20,000 spectrum analyzer and even if it was me, how else can we be sure Hewlett-Packard built it right in the first place unless it gets tested properly?" |

Having spent a fortune on the Acania, and finally her wonderful radars all worked, and the fresh water distillation plant as well we could not exactly decommission her and leave the Navy without a ship! So Mr. Van Nevery got us work in the Caribbean watching missile launches from Cape Canaveral and IRBM re-entries at Antigua. (All this led to OTH radars, the Army's DAMP ship and such--other chapters of the RPL daga). I flew a KLM DC6 to Bermuda and Curacao through an Atlantic hurricane in 1960 and joined the ship there. She was soon to be under the command of First Mate Woody Reynolds who lovingly cared for the ship thereafter for many years, finally ending his maritime career after a long stint of duty skippering the Acania as an oceanographic research vessel for the Navy Postgraduate school at Monterey. (Last I heard this wonderful ship was still in service back in Alaskan waters. She will be 70 years old next year). Anyway back in '60 we sailed across the Caribbean (pitch, roll, lurch, crash, heave) finally anchoring safely at Antigua.

Mr. Leadabrand flew down to the British West Indies (still Pan Am, by the way, now DC6s--they did not apparently have any stratocrashers left). The high point of our time in Antigua was a ride on the sugar cane train with lots of rum and a wonderful on-board steel-drum band. "We all work hard but when it is time to play we play hard also," Ray often said. The native girls at Antigua, each black as midnight, came to the pier every night at dusk to pick up our laundry. At night they were totally invisible on the dock so we had to yell to see if they were there. Arch McKinley made many friends in town and got to know everyone on a first name basis and the local culture was always a source of much frivolity and fantail discussions before dinner. Our next work with the Acania was at West Palm Beach and Ft. Pierce and then out to the Bahamas to watch with radar missile exhaust trails in the upper atmosphere. I left Roy Long to do the real work and spent time "resting" in Menlo Park (We called it "writing reports"). It was not easy getting out to the ship when it was at Eleuthra but I discovered that my International Air Travel Car would buy me charter plane service by seaplane from Miami, so I came and went in high style just in take to plagiarize the data and the final results to take to Mr. Van Avery.

Michael Victor Acania at Johnston Island, 1958

The Acania went on serving us and our Glorious Leader into the early 60's--including the above-mentioned second nuclear test series when the Good Ship was in Samoa. My last trip with her was 40 days in the South seas out of Samoa in 1962 or 63. George Durfey had preceded me and during our transition time in Samoa I shall never forgot our night at a native banquet and feast at a remote village. Later our Captain (Woody) took the ship out to a remote island for our own fun day of experiencing native life in the style of Margaret Mead. So much for the South Seas...

Our

work at RPL with spark transmitters continued. Ray L. Leadabrand

was "kicked upstairs" to be the head of the engineering

division and young Dave Johnson (daj) assumed the helm of the

RPL. Ever friendly, easy going, Dave was an immediately very popular

Giant Leader for our motley crew, now a lab of about a hundred

souls. Dr. Alec Montflower Patterson--One and Two--continued to

drop by answering three phone calls simultaneously while pacing

back and forth discussing the future of the human race in casual,

cryptic terms, "I'll see the President in the morning and

see what we can do about some extra funding. I suppose another

250k should tide you over for a few weeks?' Public Relations became

more and more important over the years at SRI as more good people

moved up into Higher management and populated the walnut paneled

offices of Building One. Most of us did not venture there except

for occasional command performances. We just worked away grateful

for Mr. Leadabrand and Dave Johnson being Firewalls to protect

us from the outside world, and especially from the Central Staff

(whoever they were).

Our

work at RPL with spark transmitters continued. Ray L. Leadabrand

was "kicked upstairs" to be the head of the engineering

division and young Dave Johnson (daj) assumed the helm of the

RPL. Ever friendly, easy going, Dave was an immediately very popular

Giant Leader for our motley crew, now a lab of about a hundred

souls. Dr. Alec Montflower Patterson--One and Two--continued to

drop by answering three phone calls simultaneously while pacing

back and forth discussing the future of the human race in casual,

cryptic terms, "I'll see the President in the morning and

see what we can do about some extra funding. I suppose another

250k should tide you over for a few weeks?' Public Relations became

more and more important over the years at SRI as more good people

moved up into Higher management and populated the walnut paneled

offices of Building One. Most of us did not venture there except

for occasional command performances. We just worked away grateful

for Mr. Leadabrand and Dave Johnson being Firewalls to protect

us from the outside world, and especially from the Central Staff

(whoever they were).

Dave's management style in our lab was easy going. He liked teams and management retreats.

RPL Lab Managers' Retreat at Pajarro Dunes during the

David A. Johnson Administration

Dave fostered more spark gap transmitter

work. I built huge wooden rings outside the high bay that ran

on 100 kv x-ray transformers. We hoped  to develop pulses

at HF large enough to be seen by satellites, and to a modest extent

we exceeded. But in spite of huge wooden wine vans filled with

transformer oil and pressurized spark gaps triggered by UV light

supplied from banks of thyratrons, we could not sync a multliplicity

of spark gaps to get the single coherent pulse we hoped for. Dr.

Oetzel came to our rescue and built some water filled coax sections

that generated fairly hefty pulse so lots of hard work and investment

did yield a good understanding on things and some minor applications

to early high power RF pulse technology. Mad scientist Doldrums

insisted everyone working around high voltage be properly equipped

with corona ear-protectors, and Art Wickersham ran off to patent

125 useless high voltage circuits that he was sure worked or could

be made to work if he could simply get us to learn Maxwell's equations

correctly. Howard Young proceeded to work alone inside the high

voltage cages at lunch time zapping himself several times, but

somehow rejuvenating his brain every time. Archie McKinley was

also nonchalant around high power stuff and he was never startled

when the fuses blew in the building. Ron PreTzel led a popular

movement to keep all the delicate instruments locked up where

I could not get to them and Lee Lumbard in the machine shop had

an alarm button he could push when he saw me coming to use a lathe

or milling machine. There was actually real, honest, legitimate

science going on in our lab by reputable people, but I steered

away from such things.

to develop pulses

at HF large enough to be seen by satellites, and to a modest extent

we exceeded. But in spite of huge wooden wine vans filled with

transformer oil and pressurized spark gaps triggered by UV light

supplied from banks of thyratrons, we could not sync a multliplicity

of spark gaps to get the single coherent pulse we hoped for. Dr.

Oetzel came to our rescue and built some water filled coax sections

that generated fairly hefty pulse so lots of hard work and investment

did yield a good understanding on things and some minor applications

to early high power RF pulse technology. Mad scientist Doldrums

insisted everyone working around high voltage be properly equipped

with corona ear-protectors, and Art Wickersham ran off to patent

125 useless high voltage circuits that he was sure worked or could

be made to work if he could simply get us to learn Maxwell's equations

correctly. Howard Young proceeded to work alone inside the high

voltage cages at lunch time zapping himself several times, but

somehow rejuvenating his brain every time. Archie McKinley was

also nonchalant around high power stuff and he was never startled

when the fuses blew in the building. Ron PreTzel led a popular

movement to keep all the delicate instruments locked up where

I could not get to them and Lee Lumbard in the machine shop had

an alarm button he could push when he saw me coming to use a lathe

or milling machine. There was actually real, honest, legitimate

science going on in our lab by reputable people, but I steered

away from such things.

Another fabricated, false, misleading, scandalous

story generated by the fertile imagination of one Jim Hodges.

Friends of Commodore Doldrums and of his secretary Eunice Loibel

(aka E Pluribus Unis) deny all these wild stories. The weakly

concealed allusion to Granger Associates does not escape our notice.

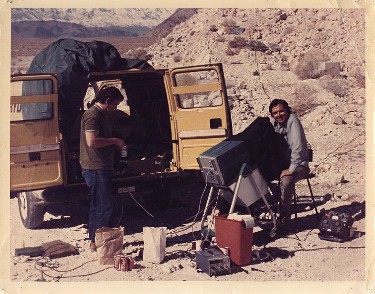

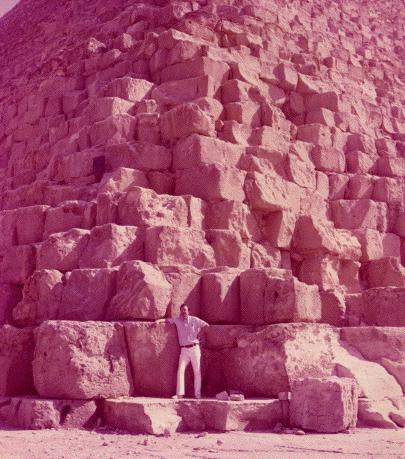

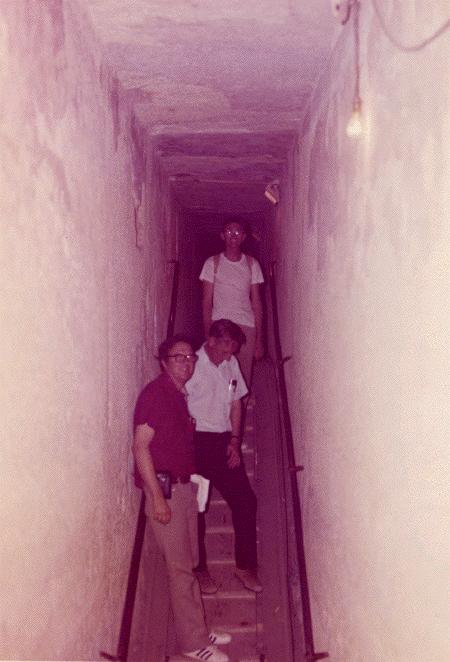

Along about

1972, Dave thought Art Wickersham and Bob Bollen and George Oatmeal

and I should see what we could do turning radars downward into

the earth rather than outwards towards the ionosphere and outer

space. Thus began the Nortonville Coal Mine era of radar development

research conducted at Mount Diablo across the Bay. We explored

the miles of old underground tunnels (last used in 1885) and tried

all possible radar antennas and spark gaps. Bill Edson suggested

slot antennas covered by copper cages so we lugged these in vain

up and down the hills at Nortonville for many months. Joining

us was Sharon S. O. ("Buck") Buckingham, right hand

man of Prof. Luis Alvarez of UC Berkeley Labs. Luis had called

me into his office in 1973 and handed me a piece of casing limestone

from the great pyramid of Giza. He told us about his labors to

look for hidden chambers in the pyramid of Chephren by counting

directional cosmic rays in the burial chamber. He thought we ought

to build a radar for the pyramids. The limestone sample had low

radar losses when tested in the lab, little did we know that the

real pyramids are wet and very attenuative as far as radar is

concerned. Finally after trials in the open pit mine at Boron,

California (below left), we succeeded in 1973 with Dr. Oatmeal's

brilliant help, in getting our first spark gap transmitter to

work. Our field site (below) was an old dolomite mine near Lone

Pine in the Owens Valley.

Along about

1972, Dave thought Art Wickersham and Bob Bollen and George Oatmeal

and I should see what we could do turning radars downward into

the earth rather than outwards towards the ionosphere and outer

space. Thus began the Nortonville Coal Mine era of radar development

research conducted at Mount Diablo across the Bay. We explored

the miles of old underground tunnels (last used in 1885) and tried

all possible radar antennas and spark gaps. Bill Edson suggested

slot antennas covered by copper cages so we lugged these in vain

up and down the hills at Nortonville for many months. Joining

us was Sharon S. O. ("Buck") Buckingham, right hand

man of Prof. Luis Alvarez of UC Berkeley Labs. Luis had called

me into his office in 1973 and handed me a piece of casing limestone

from the great pyramid of Giza. He told us about his labors to

look for hidden chambers in the pyramid of Chephren by counting

directional cosmic rays in the burial chamber. He thought we ought

to build a radar for the pyramids. The limestone sample had low

radar losses when tested in the lab, little did we know that the

real pyramids are wet and very attenuative as far as radar is

concerned. Finally after trials in the open pit mine at Boron,

California (below left), we succeeded in 1973 with Dr. Oatmeal's

brilliant help, in getting our first spark gap transmitter to

work. Our field site (below) was an old dolomite mine near Lone

Pine in the Owens Valley.

![]()

|

|

Dave Johnson tried, always to be understanding and helpful. He loved field trips to exotic desert places such as Randsburg and Burro Schmidt's tunnel and Red Rock Canyon. "Lambert, are you sure that is a genuine petrified dinosaur leg there in the rock? If this is another one of your wild goose chases Mr. Leaderband will not be happy with us. But I'll call John Golden in Washington and have set up meetings for you and Bob Bollen at the Smithsonian so you can present this to them and also to Congress. Pete is meeting with the Joint Chiefs on Monday and he will want them to know about this. Thank God Hilly is out of town or he would jump right on top of this one. If this isn't a petrified dinosaur at least it is a great mine shaft we almost fell into out here. Let's go have a beer and sort this one out at California City in the bar. As Ray taught us, 'we work hard but we also play hard.'"

Alvarez sent me off to NSF to find modest funds for Egypt and a wonderful kindly Project Monitor Selim Selcuk at NSF went out of his way to find us a few US dollars--and a lot of Egyptian pounds. It would appear that the last of the big spenders was not as yet all washed up. To help spend pounds Buckingham came along on our first trip to Egypt in 1974. When our equipment got to Cairo it was scattered far and wide over a huge warehouse all in isolated pieces. Stepping into the customs clearing house at the airport, Buck threw a huge handful of piasters into the air. Landing with a clatter all over the stone floor he immediately hired a hundred workers and several large trucks and soon had all our precious radar equipment safely in the Guest House at Giza, out among the tombs of Cheop's court officials. So began the first of three exciting field trips to Egypt--1974, 1976 and 1978. Including other trips (with DAJ to Teheran for instance) I have made 14 trips to Cairo and it came to feel like a second home. This is especially so since as Roger Vickers and Patty Crawley Burns will testify, our field teams also lived in "SherAtone quality" housing--enjoying every amenity and luxury of high society in Cairo.

Bollen, Doldrums, Oetzel discuss dielctric constantts of wet

Giza Limestone

|

"My

head hurts, I can't tell whether this rock measures 400 or 4000

ohms." |

"Lambert, you can't tell me this model pyramid sharpens razor blades? I'll never believe it!"

|

Some Government

Projects are invariably "Blackops" for which trained

security professionals are on duty 24/7/365.25

"Yes the echo is coming from the mummy chamber and there is something moving there." |

""Deliver the camel to Dave Johnson at the Sheraton. I think you can get it on the service elevator." |

|

|